Reading Notes

4 Naive Bayes and Sentiment Classification

In this chapter we introduce the naive Bayes algorithm and apply it to text categorization, the task of assigning a label or category to an entire text or document.

We focus on one common text categorization task, sentiment analysis, the extraction of sentiment, the positive or negative orientation that a writer expresses toward some object.

Spam detection is another important commercial application, the binary classification task of assigning an email to one of the two classes spam or not-spam.

4.1 Naive Bayes Classifier

In this section we introduce the multinomial naive Bayes classifier, so called be- cause it is a Bayesian classifier that makes a simplifying (naive) assumption about how the features interact.

bag-of-words: an unordered set of words with their position ignored, keeping only their frequency in the document.

\[\hat{c}=\underset{c \in C}{\operatorname{argmax}} P(c | d)=\underset{c \in C}{\operatorname{argmax}} \frac{P(d | c) P(c)}{P(d)}\]$d$ is document, $c$ is class, $\hat{c}$ is our best estimated class.

\[\hat{c}=\underset{c \in C}{\operatorname{argmax}} \quad \overbrace{P(d | c)}^{\text {likelihood}} \quad \overbrace{P(c)}^{\text{prior}}\]We thus compute the most probable class $\hat{c}$ given some document $d$ by choosing the class which has the highest product of two probabilities: the prior probability of the class $P(c)$ and the likelihood of the document $P(d c):$ Without loss of generalization, we can represent a document $d$ as a set of features $f_{1}, f_{2}, \ldots, f_{n}:$

\[\hat{c}=\underset{c \in C}{\operatorname{argmax}} \quad \overbrace{P\left(f_{1}, f_{2}, \ldots, f_{n} | c\right)}^{\text {likelihood }} \quad \overbrace{P(c)}^{\text {prior }}\]Naive Bayes classification make two simplifying assumptions:

The first is the bag of words assumption discussed intuitively above: we assume position doesn’t matter, and that the word “love” has the same effect on classification whether it occurs as the 1st, 20th, or last word in the document.

\[P\left(f_{1}, f_{2}, \ldots, f_{n} | c\right)=P\left(f_{1} | c\right) \cdot P\left(f_{2} | c\right) \cdot \ldots \cdot P\left(f_{n} | c\right)\]The second is commonly called the naive Bayes assumption: this is the conditional independence assumption that the probabilities $P\left(f_{i} c\right)$ are independent given the class $c$ and hence can be ‘naively’ multiplied as follows: Then, we have simplified of previous formula:

\[c_{N B}=\underset{c \in C}{\operatorname{argmax}} P(c) \prod_{f \in F} P(f | c)\]To apply the naive Bayes classifier to text, we need to consider word positions, by simply walking an index through every word position in the document:

\[c_{N B}=\underset{c \in C}{\operatorname{argmax}} P(c) \prod_{i \in positions} P\left(w_{i} | c\right)\]

positions $\leftarrow$ all word positions in test documentTo avoid underflow, like calculations for language modeling, are done in log space.

\[c_{N B}=\underset{c \in C}{\operatorname{argmax}} \log P(c)+\sum_{i \in \text {positions}} \log P\left(w_{i} | c\right)\]like naive Bayes and also logistic regression— are called linear classifiers.

4.2 Training the Naive Bayes Classifier

How can we learn the probabilities $P(c)$ and $P\left(f_{i} c\right) ?$ Let $N_{c}$ be the number of documents in our training data with class $c$ and $N_{d o c}$ be the total number of documents. Then:

\[\hat{P}(c)=\frac{N_{c}}{N_{d o c}}\]\[\hat{P}\left(w_{i} | c\right)=\frac{\operatorname{count}\left(w_{i}, c\right)}{\sum_{w \in V} \operatorname{count}(w, c)}\]To learn the probability $P\left(f_{i} c\right),$ we’ll assume a feature is just the existence of a word in the document’s bag of words, and so we’ll want $P\left(w_{i} c\right),$ which we compute as the fraction of times the word $w_{i}$ appears among all words in all documents of topic c. We first concatenate all documents with category $c$ into one big “category $c^{\prime \prime}$ text. Then we use the frequency of $w_{i}$ in this concatenated document to give a maximum likelihood estimate of the probability: But since naive Bayes naively multiplies all the feature likelihoods together, zero probabilities in the likelihood term for any class will cause the probability of the class to be zero, no matter the other evidence! The simplest solution is the add-one (Laplace) smoothing. While Laplace smoothing is usually replaced by more sophisticated smoothing algorithms in language modeling, it is commonly used in naive Bayes text categorization:

\[\hat{P}\left(w_{i} | c\right)=\frac{\operatorname{count}\left(w_{i}, c\right)+1}{\sum_{w \in V}(\operatorname{count}(w, c)+1)}=\frac{\operatorname{count}\left(w_{i}, c\right)+1}{\left(\sum_{w \in V} \operatorname{count}(w, c)\right)+|V|}\]Note once again that it is crucial that the vocabulary V consists of the union of all the word types in all classes, not just the words in one class c.

4.4 Optimizing for Sentiment Analysis

First, for sentiment classification and a number of other text classification tasks, whether a word occurs or not seems to matter more than its frequency. Thus it often improves performance to clip the word counts in each document at 1.

Binary multinomial naive Bayes or binary NB: remove all duplicate words before concatenating them into the single big document.

A second important addition commonly made when doing text classification for sentiment is to deal with negation. The negation expressed by didn’t completely alters the inferences we draw from the predicate like.

Finally, in some situations we might have insufficient labeled training data to train accurate naive Bayes classifiers using all words in the training set to estimate positive and negative sentiment

we can instead derive the positive and negative word features from sentiment lexicons, lists of words that are pre- annotated with positive or negative sentiment.

7 Neural Networks and Neural Language Models

7.5 Neural Language Models

Comparison of traditional language model and neural language model.

For a training set of a given size, a neural language model has much higher predictive accuracy than an n-gram language model.

On the other hand, there is a cost for this improved performance: neural net language models are strikingly slower to train than traditional language models, and so for many tasks an n-gram language model is still the right tool.

7.5.1 Embeddings

Representing the prior context as embeddings, allows neural language models to generalize to unseen data much better than n-gram language models.

simplified feedforward neural language model with N=3:

additional layers needed to learn the embeddings during LM training. Here N=3 context words are represented as 3 one-hot vectors.

Let’s walk through the forward pass of figure above:

- Select three embeddings from E

- Multiply by W

- Multiply by U

- Apply softmax

In summary, if we use $e$ to represent the projection layer, formed by concatenating the 3 embeddings for the three context vectors, the equations for a neural language model become:

\[\begin{array}{l} {e=\left(E x_{1}, E x_{2}, \ldots, E x\right)} \\ {h=\sigma(W e+b)} \\ {z=U h} \\ {y=\operatorname{softmax}(z)} \end{array}\]7.5.2 Training the neural language model

Generally training proceeds by taking as input a very long text, concatenating all the sentences, starting with random weights, and then iteratively moving through the text predicting each word $w_{t} .$ At each word $w_{t},$ the cross-entropy (negative log likelihood) loss is:

\[L=-\log p\left(w_{t} | w_{t-1}, \dots, w_{t-n+1}\right)\]The gradient for this loss is then:

\[\theta_{t+1}=\theta_{t}-\eta \frac{\partial-\log p\left(w_{t} | w_{t-1}, \ldots, w_{t-n+1}\right)}{\partial \theta}\]

9 Sequence Processing with Recurrent Networks

In contrast, the machine learning approaches we’ve studied for sentiment analysis and other classification tasks do not have this temporal nature.

9.1 Simple Recurrent Neural Networks

9.1.1 Inference in Simple RNNs

\[\begin{array}{l} {h_{t}=g\left(U h_{t-1}+W x_{t}\right)} \\ {y_{t}=f\left(V h_{t}\right)} \end{array}\]In the commonly encountered case of soft classification, computing $y_{t}$ consists of a softmax computation that provides a normalized probability distribution over the possible output classes.

\[y_{t}=\operatorname{softmax}\left(V h_{t}\right)\]9.1.2 Training

\[\frac{\partial L}{\partial V}=\frac{\partial L}{\partial a} \frac{\partial a}{\partial z} \frac{\partial z}{\partial V}\]The final term $\frac{\partial z}{\partial V}$ in our application of the chain rule is the derivative of the network activation with respect to the weights $V,$ which is the activation value of the current hidden layer $h_{t}$

It’s useful here to use the first two terms to define $\delta,$ an error term that represents how much of the scalar loss is attributable to each of the units in the output layer.

\[\begin{aligned} &\delta_{o u t}=\frac{\partial L}{\partial a} \frac{\partial a}{\partial z}\\ &\delta_{o u t}=L^{\prime} g^{\prime}(z) \end{aligned}\]Therefore, the final gradient we need to update the weight matrix $V$ is just:

\[\frac{\partial L}{\partial V}=\delta_{o u t} h_{t}\]Moving on, we need to compute the corresponding gradients for the weight matrices $W$ and $U: \frac{\partial L}{\partial W}$ and $\frac{\partial L}{\partial U} .$ Here we encounter the first substantive change from feedforward networks. The hidden state at time $t$ contributes to the output and associated error at time $t$ and to the output and error at the next time step, $t+1 .$ Therefore, the error term, $\delta_{h},$ for the hidden layer must be the sum of the error term from the current output and its error from the next time step.

\[\delta_{h}=g^{\prime}(z) V \delta_{o u t}+\delta_{n e x t}\]Where $V = \frac{\partial z}{\partial h}$, and $h_t$ is activations after applying $g(U\times h_{t-1}+W\times x_t)$, so we add $g’(z)$

\[\begin{array}{l} {\frac{d L}{d W}=\frac{d L}{d z} \frac{d z}{d a} \frac{d a}{d W}} \\ {\frac{d L}{d U}=\frac{d L}{d z} \frac{d z}{d a} \frac{d a}{d U}} \end{array}\] \[\begin{array}{l} {\frac{\partial L}{\partial W}=\delta_{h} x_{t}} \\ {\frac{\partial L}{\partial U}=\delta_{h} h_{t-1}} \end{array}\]We’re not quite done yet, we still need to assign proportional blame (compute the error term) back to the previous hidden layer $h_{t-1}$ for use in further processing. This involves backpropagating the error from $\delta_{h}$ to $h_{t-1}$ proportionally based on the weights in $U$

\[\delta_{n e x t}=g^{\prime}(z) U \delta_{h}\]Where is similar to $h_t$ we explained above, we need to add $g’(z)$

9.1.3 Unrolled Networks as Computation Graphs

9.2 Applications of Recurrent Neural Networks

9.2.1 Recurrent Neural Language Models

In both approaches, the quality of a model is largely dependent on the size of the context and how effectively the model makes use of it. Thus, both $N$ -gram and sliding-window neural networks are constrained by the Markov assumption embodied in the following equation.

\[P\left(w_{n} | w_{1}^{n-1}\right) \approx P\left(w_{n} | w_{n-N+1}^{n-1}\right)\]This hidden layer is then used to generate an output which is passed through a softmax layer to generate a probability distribution over the entire vocabulary.

\[\begin{aligned} P\left(w_{n} | w_{1}^{n-1}\right) &=y_{n} \\ &=\operatorname{softmax}\left(V h_{n}\right) \end{aligned}\]The probability of an entire sequence is then just the product of the probabilities of each item in the sequence.

\[\begin{aligned} P\left(w_{1}^{n}\right) &=\prod_{k=1}^{n} P\left(w_{k} | w_{1}^{k-1}\right) \\ &=\prod_{k=1}^{n} y_{k} \end{aligned}\]Recall that the cross-entropy loss for a single example is the negative log probability assigned to the correct class, which is the result of applying a softmax to the final output layer.

\[\begin{aligned} L_{C E}(\hat{y}, y) &=-\log \hat{y}_{i} \\ &=-\log \frac{e^{z_{i}}}{\sum_{j=1}^{K} e^{z_{j}}} \end{aligned}\]Generation with Neural Language Models

$\cdot$ To begin, sample the first word in the output from the softmax distribution that results from using the beginning of sentence marker, $<\mathrm{s}>,$ as the first input.

$\cdot$ Use the word embedding for that first word as the input to the network at the next time step, and then sample the next word in the same fashion.

$\cdot$ Continue generating until the end of sentence marker, $</ \mathrm{s}>,$ is sampled or a fixed length limit is reached.This technique is called autoregressive generation since the word generated at the each time step is conditioned on the word generated by the network at the previous step.

assessing the quality of generated output by using perplexity to objectively compare the output to a held-out sample of the training corpus.

The lower the perplexity, the better the model.

\[\operatorname{PP}(W)=\sqrt[N]{\prod_{i=1}^{N} \frac{1}{P\left(w_{i} | w_{i-1}\right)}}\]9.2.2 Sequence Labeling

Viterbi and Conditional Random Fields(CRFs)

As we saw when we applied logistic regression to part-of-speech tagging, choosing the maximum probability label for each element in a sequence independently does not necessarily result in an optimal (or even very good) sequence of tags.

9.2.3 RNNs for Sequence Classification

Another use of RNNs is to classify entire sequences rather than the tokens within them.

And the training regimen that uses the loss from a downstream application to adjust the weights all the way through the network is referred to as end-to-end training.

9.3 Deep Networks: Stacked and Bidirectional RNNs

9.3.1 Stacked RNNs

9.3.2 Bidirectional RNNs

We can think of this as the context of the network to the left of the current time.

\[h_{t}^{f}=R N N_{\text {forward}}\left(x_{1}^{t}\right)\]Where $h_{t}^{f}$ corresponds to the normal hidden state at time $t,$ and represents everything the network has gleaned from the sequence to that point.

One way to recover such information is to train an RNN on an input sequence in reverse, using exactly the same kind of networks that we’ve been discussing. With this approach, the hidden state at time $t$ now represents information about the sequence to the right of the current input.

\[h_{t}^{b}=R N N_{\text{backward}}\left(x_{t}^{n}\right)\]Combining the forward and backward networks results in a bidirectional RNN. A Bi-RNN consists of two independent RNNs, one where the input is processed from the start to the end, and the other from the end to the start. We then combine the outputs of the two networks into a single representation that captures both the left and right contexts of an input at each point in time.

\[h_{t}=h_{t}^{f} \oplus h_{t}^{b}\]

9.4 Managing Context in RNNs: LSTMs and GRUs

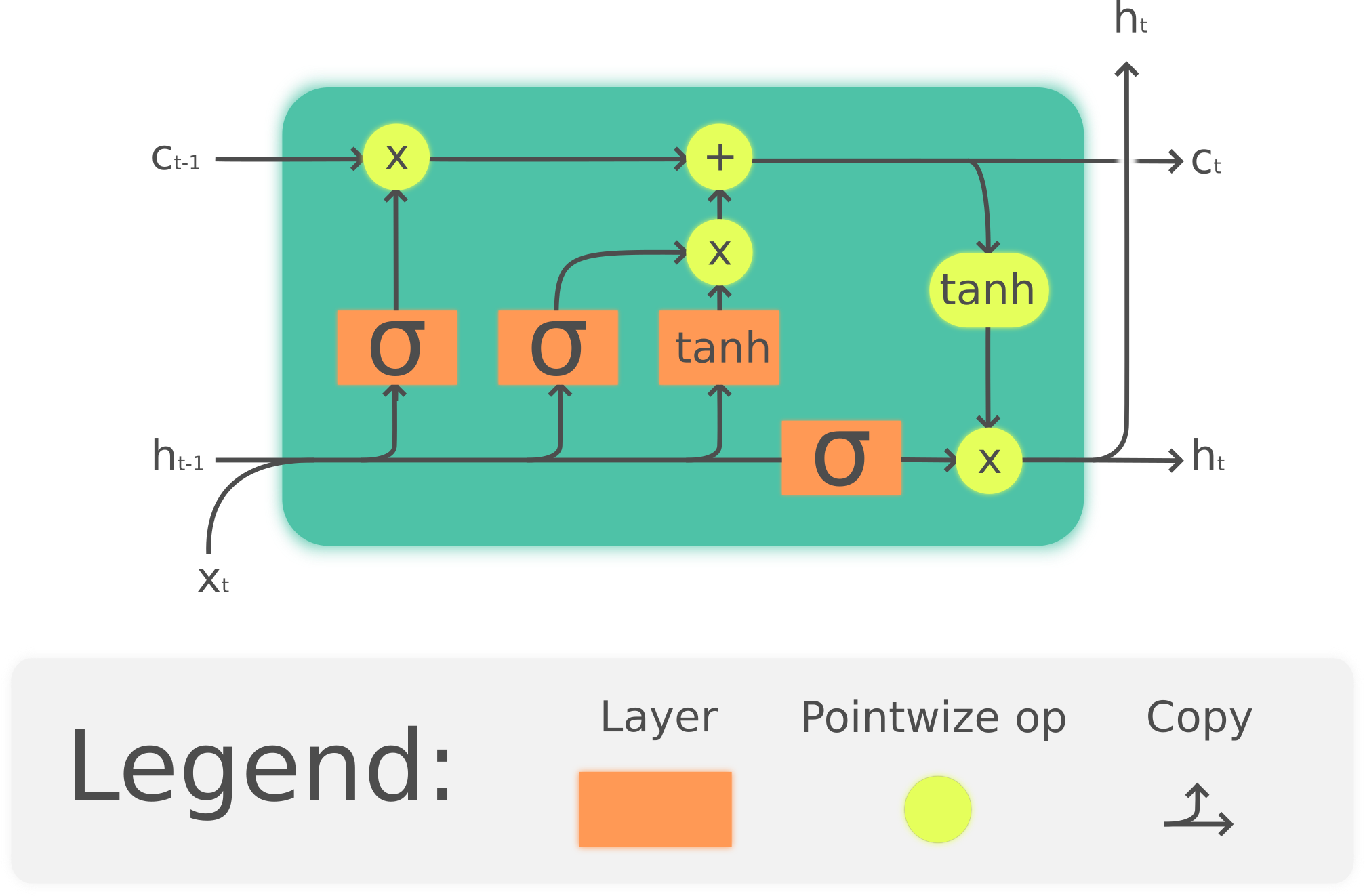

9.4.1 Long Short-Term Memory

The gates in an LSTM share a common design pattern; each consists of a feed- forward layer, followed by a sigmoid activation function, followed by a pointwise multiplication with the layer being gated. Combining this with a pointwise multiplication has an effect similar to that of a binary mask. Values in the layer being gated that align with values near 1 in the mask are passed through nearly unchanged; values corresponding to lower values are essentially erased.

The first gate we’ll consider is the forget gate.

\[\begin{array}{l} {f_{t}=\sigma\left(U_{f} h_{t-1}+W_{f} x_{t}\right)} \\ {k_{t}=c_{t-1} \odot f_{t}} \end{array}\]The next task is compute the actual information we need to extract from the previous hidden state and current inputs.

\[g_{t}=\tanh \left(U_{g} h_{t-1}+W_{g} x_{t}\right)\]Next, we generate the mask for the add gate to select the information to add to the current context.

\[\begin{aligned} i_{t} &=\sigma\left(U_{i} h_{t-1}+W_{i} x_{t}\right) \\ j_{t} &=g_{t} \odot i_{t} \end{aligned}\]Next, we add this to the modified context vector to get our new context vector.

\[c_{t}=j_{t}+k_{t}\]The final gate we’ll use is the output gate which is used to decide what information is required for the current hidden state.

\[\begin{array}{l} {o_{t}=\sigma\left(U_{o} h_{t-1}+W_{o} x_{t}\right)} \\ {h_{t}=o_{t} \odot \tanh \left(c_{t}\right)} \end{array}\]LSTMs introduce a considerable number of additional parameters to our recurrent networks. We now have 8 sets of weights to learn (i.e., the U and W for each of the 4 gates within each unit)

9.4.2 Gated Recurrent Units

GRUs ease this burden by dispensing with the use of a separate context vector, and by reducing the number of gates to $2-$ a reset gate, $r$ and an update gate, $z$.

\[\begin{array}{l} {r_{t}=\sigma\left(U_{r} h_{t-1}+W_{r} x_{t}\right)} \\ {z_{t}=\sigma\left(U_{z} h_{t-1}+W_{z} x_{t}\right)} \end{array}\]The purpose of the reset gate is to decide which aspects of the previous hidden state are relevant to the current context and what can be ignored.

This is accomplished by performing an element-wise multiplication of $r$ with the value of the previous hidden state.

\[\tilde{h_{t}}=\tanh \left(U\left(r_{t} \odot h_{t-1}\right)+W x_{t}\right)\]The job of the update gate z is to determine which aspects of this new state will be used directly in the new hidden state and which aspects of the previous state need to be preserved for future use.

\[h_{t}=\left(1-z_{t}\right) h_{t-1}+z_{t} \tilde{h}_{t}\]9.4.3 Gated Units Layers and Networks

Problems:

- For some languages and applications, the lexicon is simply too large to practically represent every possible word as an embedding. Some means of com- posing words from smaller bits is needed.

- No matter how large the lexicon, we will always encounter unknown words due to new words entering the language, misspellings and borrowings from other languages.

- Morphological information, below the word level, is a critical source of information for many languages and many applications. Word-based methods are blind to such regularities.

Solutions:

- Ignore words altogether and simply use character sequences as the input to RNNs.

- Use subword units such as those derived from byte-pair encoding or phonetic analysis as inputs.

- Use full-blown morphological analysis to derive a linguistically motivated in- put sequence.

9.5 Words, Subwords and Characters

10 Encoder-Decoder Models, Attention, and Contextual Embeddings

10.1 Neural Language Models and Generation Revisited

To understand the design of encoder-decoder networks let’s return to neural language models and the notion of autoregressive generation.

Now, let’s consider a simple variation on this scheme. Instead of having the language model generate a sentence from scratch. We then begin generating as we did earlier, but using the final hidden state of the prefix as our starting point. The portion of the network on the left processes the provided prefix, while the right side executes the subsequent auto- regressive generation.

Now, consider an ingenious extension of this idea from the world of machine translation (MT).

To extend language models and autoregressive generation to machine translation, we’ll first add an end-of-sentence marker at the end of each bitext’s source sentence. simply concatenate the corresponding target to it. Then these are our training data.

10.2 Encoder-Decoder Networks

Abstracting away from these choices, we can say that encoder-decoder networks consist of three components:

- An encoder that accepts an input sequence, $x_{1}^{n},$ and generates a corresponding sequence of contextualized representations, $h_{1}^{n}$

- A context vector, $c,$ which is a function of $h_{1}^{n},$ and conveys the essence of the input to the decoder.

- And a decoder, which accepts $c$ as input and generates an arbitrary length sequence of hidden states $h_{1}^{m},$ from which a corresponding sequence of output states $y_{1}^{m},$ can be obtained.

Encoder

A widely used encoder design makes use of stacked Bi-LSTMs where the hidden states from top layers from the forward and backward passes are concatenated.

Decoder

For the decoder, autoregressive generation is used to produce an output sequence, an element at a time, until an end-of-sequence marker is generated.

A typical approach is to use an LSTM or GRU-based RNN where the context consists of the final hidden state of the encoder, and is used to initialize the first hidden state of the decoder.

we’ll use the superscripts $e$ and $d$ where needed to distinguish the hidden states of the encoder and the decoder.

\[\begin{aligned} c &=h_{n}^{e} \\ h_{0}^{d} &=c \\ h_{t}^{d} &=g\left(\hat{y}_{t-1}, h_{t-1}^{d}\right) \\ z_{t} &=f\left(h_{t}^{d}\right) \\ y_{t} &=\operatorname{softmax}\left(z_{t}\right) \end{aligned}\]A weakness of this approach is that the context vector, c, is only directly avail- able at the beginning of the process and its influence will wane as the output sequence is generated.

A solution is to make the context vector $c$ available at each step in the decoding process by adding it as a parameter to the computation of the current hidden state.

\[h_{t}^{d}=g\left(\hat{y}_{t-1}, h_{t-1}^{d}, c\right)\]A common approach to the calculation of the output layer $y$ is to base it solely on this newly computed hidden state. While this cleanly separates the underlying recurrence from the output generation task, it makes it difficult to keep track of what has already been generated and what hasn’t. A alternative approach is to condition the output on both the newly generated hidden state, the output generated at the previous state, and the encoder context.

\[y_{t}=\operatorname{softmax}\left(\hat{y}_{t-1}, z_{t}, c\right)\]Finally, as shown earlier, the output $y$ at each time consists of a softmax computation over the set of possible outputs (the vocabulary in the case of language models). What one does with this distribution is task-dependent, but it is critical since the recurrence depends on choosing a particular output, $\hat{y},$ from the softmax to condition the next step in decoding. We’ve already seen several of the possible options for this. For neural generation, where we are trying to generate novel outputs, we can simply sample from the softmax distribution. However, for applications like MT where we’re looking for a specific output sequence, random sampling isn’t appropriate and would likely lead to some strange output. An alternative is to choose the most likely output at each time step by taking the argmax over the softmax output:

\[\hat{y}=\operatorname{argmax} P\left(y_{i} | y_{<} i\right)\]Beam Search

A viable alternative is to view the decoding problem as a heuristic state-space search and systematically explore the space of possible outputs.

Context

We’ve defined the context vector $c$ as a function of the hidden states of the encoder, that is, $c=f\left(h_{1}^{n}\right) .$ Use Bi-RNNs, where the context can be a function of the end state of both the forward and backward passes. Unfortunately, this approach loses useful information about each of the individual encoder states that might prove useful in decoding.

10.3 Attention

To overcome the deficiencies of these simple approaches to context, we’ll need a mechanism that can take the entire encoder context into account, that dynamically updates during the course of decoding, and that can be embodied in a fixed-size vector. Taken together, we’ll refer such an approach as an attention mechanism.

Our first step is to replace the static context vector with one that is dynamically derived from the encoder hidden states at each point during decoding. This context vector $c_i$ is generated anew(a new one) with each decoding step $i$ and takes all of the encoder hidden states into account in its derivation.

\[h_{i}^{d}=g\left(\hat{y}_{i-1}, h_{i-1}^{d}, c_{i}\right)\]The first step in computing $c_{i}$ is to compute a vector of scores that capture the relevance of each encoder hidden state to the decoder state captured in $h_{i-1}^{d} .$ That is, at each state $\left.i \text { during decoding we’ll compute score( } h_{i-1}^{d}, h_{j}^{e}\right)$ for each encoder state $j$.

For now, let’s assume that this score provides us with a measure of how similar the decoder hidden state is to each encoder hidden state. To implement this similarity score, let’s begin with the straightforward approach introduced in Chapter 6 of using the dot product between vectors.

\[\operatorname{score}\left(h_{i-1}^{d}, h_{j}^{e}\right)=h_{i-1}^{d} \cdot h_{j}^{e}\]The result of the dot product is a scalar that reflects the degree of similarity between the two vectors. While the simple dot product can be effective, it is a static measure that does not facilitate adaptation during the course of training to fit the characteristics of given applications. A more robust similarity score can be obtained by parameterizing the score with its own set of weights, $W_{s}$

\[\operatorname{score}\left(h_{i-1}^{d}, h_{j}^{e}\right)=h_{t-1}^{d} W_{s} h_{j}^{e}\]To make use of these scores, we’ll next normalize them with a softmax to create a vector of weights, $\alpha_{i j},$ that tells us the proportional relevance of each encoder hidden state $j$ to the current decoder state, $i .$

\[\begin{aligned} \alpha_{i j} &=\operatorname{softmax}\left(\operatorname{score}\left(h_{i-1}^{d}, h_{j}^{e}\right) \forall j \in e\right) \\ &=\frac{\exp \left(\operatorname{score}\left(h_{i-1}^{d}, h_{j}^{e}\right)\right.}{\sum_{k} \exp \left(\operatorname{score}\left(h_{i-1}^{d}, h_{k}^{e}\right)\right)} \end{aligned}\]Finally, given the distribution in $\alpha,$ we can compute a fixed-length context vector for the current decoder state by taking a weighted average over all the encoder hidden states.

\[c_{i}=\sum_{j} \alpha_{i j} h_{j}^{e}\]10.4 Applications of Encoder-Decoder Networks

10.5 Self-Attention and Transformer Networks

18 Information Extraction

18.1 Named Entity Recognition

The first step in information extraction is to detect the entities in the text. A named entity is, roughly speaking, anything that can be referred to with a proper name: a person, a location, an organization.

Recognition is difficult partly be- cause of the ambiguity of segmentation; we need to decide what’s an entity and what isn’t, and where the boundaries are. Another difficulty is caused by type ambiguity.

18.1.1 NER as Sequence Labeling

The standard algorithm for named entity recognition is as a word-by-word sequence labeling task, in which the assigned tags capture both the boundary and the type.

Introduce the three standard families of algorithms for NER tagging: feature based (MEMM/CRF), neural (bi-LSTM), and rule-based.18.1.2 A feature-based algorithm for NER

The first approach is to extract features and train an MEMM or CRF sequence model of the type.

![]()

word shape features are used to represent the abstract letter pattern of the word by mapping lower-case letters to ‘x’, upper-case to ‘X’, numbers to ’d’, and retaining punctuation.

A gazetteer is a list of place names, often providing millions of entries for locations with detailed geographical and political information.18.1.3 A neural algorithm for NER

18.1.4 Rule-based NER

One common approach is to make repeated rule-based passes over a text, allow- ing the results of one pass to influence the next.

18.1.5 Evaluation of Named Entity Recognition

The familiar metrics of recall, precision, and F1 measure are used to evaluate NER systems.

18.2 Relation Extraction

18.3 Extracting Times

In order to reason about times and dates, after we extract these temporal expressions they must be normalized—converted to a standard format so we can reason about them.

18.3.1 Temporal Expression Extraction

Temporal expressions are those that refer to absolute points in time, relative times, durations, and sets of these.

The temporal expression recognition task consists of finding the start and end of all of the text spans that correspond to such temporal expressions.

Rule-based approaches to temporal expression recognition use cascades of automata to recognize patterns at increasing levels of complexity.

Sequence-labeling approaches follow the same IOB scheme used for named- entity tags, marking words that are either inside, outside or at the beginning of a TIMEX3-delimited temporal expression with the I, O, and B tags as follows:18.3.2 Temporal Normalization

Temporal normalization is the process of mapping a temporal expression to either a specific point in time or to a duration. Points in time correspond to calendar dates, to times of day, or both.

Fully qualified date expressions contain a year, month, and day in some conventional form.

Temporal anchor. The values of temporal expressions such as today, yesterday, or tomorrow can all be computed with respect to this temporal anchor.

18.4 Extracting Events and their Times

The task of event extraction is to identify mentions of events in texts. For the purposes of this task, an event mention is any expression denoting an event or state that can be assigned to a particular point, or interval, in time.

Feature-based models use surface information like parts of speech, lexical items, and verb tense information.

![]()

18.5 Template Filling

18.5.1 Machine Learning Approaches to Template Filling

The task is generally modeled by training two separate supervised systems.

The first system decides whether the template is present in a particular sentence.

The second system has the job of role-filler extraction. A separate classifier is trained to detect each role (LEAD-AIRLINE, AMOUNT, and so on).18.5.2 Earlier Finite-State Template-Filling Systems

18.6 Summary

- Named entities can be recognized and classified by featured-based or neural sequence labeling techniques.

- Relations among entities can be extracted by pattern-based approaches, supervised learning methods when annotated training data is available, lightly supervised bootstrapping methods when small numbers of seed tuples or seed patterns are available, distant supervision when a database of relations is available, and unsupervised or Open IE methods.

- Reasoning about time can be facilitated by detection and normalization of temporal expressions through a combination of statistical learning and rule- based methods.

- Events can be detected and ordered in time using sequence models and classifiers trained on temporally-and event-labeled data like the TimeBank corpus. - Template-filling applications can recognize stereotypical situations in texts and assign elements from the text to roles represented as fixed sets of slots.

20 Semantic Role Labeling

20.1 Semantic Roles

Thematic roles are a way to capture this semantic commonality between Break- ers and Eaters. We say that the subjects of both these verbs are agents.

\[\begin{array}{ll} \hline \text { Thematic Role } & \text { Example } \\ \hline \text { AGENT } & \text { The waiter spilled the soup. } \\ \text { EXPERIENCER } & \text { John has a headache. } \\ \text { FORCE } & \text { The wind blows debris from the mall into our yards. } \\ \text { THEME } & \text { Only after Benjamin Franklin broke the ice... } \\ \text { RESULT } & \text { The city built a regulation-size baseball diamond... } \\ \text { CONTENT } & \text { Mona asked "You met Mary Ann at a supermarket?" } \\ \text { INSTRUMENT } & \text { He poached catfish, stunning them with a shocking device... } \\ \text { BENEFICIARY } & \text { Whenever Ann Callahan makes hotel reservations for her boss... } \\ \text { SOURCE } & \text { I flew in from Boston. } \\ \text { GOAL } & \text { I drove to Portland. } \\ \hline \text { Some prototypical examples of various thematic roles. } \end{array}\]

\(\begin{array}{ll} \hline \text { Thematic Role } & \text { Definition } \\ \hline \text { AGENT } & \text { The volitional causer of an event } \\ \text { EXPERIENCER } & \text { The experiencer of an event } \\ \text { FORCE } & \text { The non-volitional causer of the event } \\ \text { THEME } & \text { The participant most directly affected by an event } \\ \text { RESULT } & \text { The end product of an event } \\ \text { CONTENT } & \text { The proposition or content of a propositional event } \\ \text { INSTRUMENT } & \text { An instrument used in an event } \\ \text { BENEFICIARY } & \text { The beneficiary of an event } \\ \text { SOURCE } & \text { The origin of the object of a transfer event } \\ \text { GOAL } & \text { The destination of an object of a transfer event } \\ \hline \text { Some commonly used thematic roles with their definitions. } \end{array}\)20.2 Diathesis Alternations

The set of thematic role arguments taken by a verb is often called the thematic grid, $\theta$-grid, or case frame.

![]()

It turns out that many verbs allow their thematic roles to be realized in various syntactic positions. For example, verbs like give can realize the THEME and GOAL arguments in two different ways:

![]()

These multiple argument structure realizations (the fact that break can take AGENT, INSTRUMENT, or THEME as subject, and give can realize its THEME and GOAL in either order) are called verb alternations or diathesis alternations.20.3 Semantic Roles: Problems with Thematic Roles

Representing meaning at the thematic role level seems like it should be useful in dealing with complications like diathesis alternations. Yet it has proved quite difficult to come up with a standard set of roles, and equally difficult to produce a formal definition of roles like AGENT, THEME, or INSTRUMENT.

- The first of these options is to define generalized semantic roles that abstract over the specific thematic roles. For example, PROTO-AGENT and PROTO-PATIENT are generalized roles that express roughly agent-like and roughly patient-like meanings.

- The second direction is instead to define semantic roles that are specific to a particular verb or a particular group of semantically related verbs or nouns.

Two commonly used lexical resources that make use of these alternative versions of semantic roles. PropBank uses both protoroles and verb-specific semantic roles. FrameNet uses semantic roles that are specific to a general semantic idea called a frame.

20.4 The Proposition Back

The Proposition Bank, generally referred to as PropBank, is a resource of sentences annotated with semantic roles.

Here are some slightly simplified PropBank entries for one sense each of the verbs agree and fall.

![]()

PropBank also has a number of non-numbered arguments called ArgMs, (ArgM- TMP, ArgM-LOC, etc.)s

![]()

While PropBank focuses on verbs, a related project, NomBank (Meyers et al., 2004) adds annotations to noun predicates.

20.5 FrameNet

It would be even more useful if we could make such inferences in many more situations, across different verbs, and also between verbs and nouns. The FrameNet project is another semantic-role-labeling project that attempts to address just these kinds of problems(like the similarity among sentences).

Whereas roles in the PropBank project are specific to an individual verb, roles in the FrameNet project are specific to a frame.

What is frame? We call the holistic background knowledge that unites these words a frame.The idea that groups of words are defined with respect to some back- ground information is widespread in artificial intelligence and cognitive science, where besides frame we see related works like a mode, or even script.

A frame in FrameNet is a background knowledge structure that defines a set of frame-specific semantic roles, called frame elements. For example, the change position on a scale frame is defined as follows:

This frame consists of words that indicate the change of an Item’s position on a scale (the Attribute) from a starting point (Initial_value) to an end point (Final_value).

![]()

20.6 Semantic Role Labeling

20.6.1 A Feature-based Algorithm for Semantic Role Labeling

For each of these predicates, the algorithm examines each node in the parse tree and uses supervised classification to decide the semantic role (if any) it plays for this predicate.

- Pruning: since only a small number of the constituents in a sentence are arguments of any given predicate, many systems use simple heuristics to prune unlikely constituents.

- Identification: a binary classification of each node as an argument to be labeled or a NONE.

- Classification: a 1-of-$N$ classification of all the constituents that were labeled as arguments by the previous stage

Global Optimization

Features for Semantic Role Labeling20.6.2 A Neural Algorithm for Semantic Role Labeling

20.6.3 Evaluation of Semantic Role Labeling

20.7 Selectional Restrictions

- 20.7.1 Representing Selectional Restrictions

20.7.2 Selectional Preferences

Selectional Association

Selectional Preference via Conditional Probability

Evaluating Selectional Preferences

- 20.8 Primitive Decomposition of Predicates

- 20.9 Summary

- Semantic roles are abstract models of the role an argument plays in the event described by the predicate.

- Thematic roles are a model of semantic roles based on a single finite list of roles. Other semantic role models include per-verb semantic role lists and proto-agent/proto-patient, both of which are implemented in PropBank, and per-frame role lists, implemented in FrameNet.

- Semantic role labeling is the task of assigning semantic role labels to the constituents of a sentence. The task is generally treated as a supervised ma- chine learning task, with models trained on PropBank or FrameNet. Algorithms generally start by parsing a sentence and then automatically tag each parse tree node with a semantic role. Neural models map straight from words end-to-end.

- Semantic selectional restrictions allow words (particularly predicates) to post constraints on the semantic properties of their argument words

25 Question Answering

25.1 IR-based Factoid Question Answering

The goal of information retrieval based question answering is to answer a user’s question by finding short text segments on the web or some other collection of documents.

![]()

25.1.1 Question Processing

Some systems additionally extract further information such as:

- Answer type: the entity type(person, location, time, etc.)

- focus: the string of words in the question that is likely to be replaced by the answer in any string found.

- question type: math question or list question?

25.1.2 Query Formulation

Query formulation is the task of creating a query—a list of tokens— to send to an information retrieval system to retrieve documents that might contain answer strings.

The rules rephrase the question to make it look like a substring of possible declarative answers. The question “when was the laser invented?” might be reformulated as “the laser was invented”;25.1.3 Answer Types

Some systems make use of question classification, the task of finding the answer type, the named-entity categorizing the answer. A question like “Who founded Vir- gin Airlines?” expects an answer of type PERSON.

25.1.4 Document and Passage Retrieval

The IR query produced from the question processing stage is sent to an IR engine, resulting in a set of documents ranked by their relevance to the query.

25.1.5 Answer Extraction

This task is commonly modeled by span labeling: given a passage, identifying the span of text which constitutes an answer.

- 25.1.6 Feature-based Answer Extraction

- 25.1.7 N-gram tiling Answer Extraction

- 25.1.8 Neural Answer EXtraction

- 25.1.9 A bi-LSTM-based Reading Comprehension Algorithm

- 25.1.10 BERT-based Question Answering

25.2 Knowledge-base Question Answering

25.2.1 Rule-based Methods

For relations that are very frequent, it may be worthwhile to write handwritten rules to extract relations from the question. For example, to extract the birth-year relation, we could write patterns that search for the question word When, a main verb like born, and then extract the named entity argument of the verb.

- 25.2.2 Supervised Methods

25.2.3 Dealing with variation: Semi-Supervised Methods

For this reason, most meth- ods make some use of web text, either via semi-supervised methods like distant supervision or unsupervised methods like open information extraction.

![]()

25.3 using multiple information sources: IBM’s Watson

25.4 Evaluation of Factoid Answers

Mean Reciprocal rank(MRR)

\[\mathbf{M R R}=\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1 \text { s.t. } \operatorname{rank}_{i} \neq 0}^{N} \frac{1}{\operatorname{rank}_{i}}\]

For example if the system returned five answers but the first three are wrong and hence the highest-ranked correct answer is ranked fourth, the reciprocal rank score for that question would be $\frac{1}{4} .$ Questions with return sets that do not contain any correct answers are assigned a zero. The score of a system is then the average of the score for each question in the set. More formally, for an evaluation of a system returning a set of ranked answers for a test set consisting of $N$ questions, the MRR is defined asMetrics in SQuAD dataset:

- Exact match: The percentage of predicted answers that match the gold answer exactly.

- $\mathrm{F}{1}$ score: The average overlap between predicted and gold answers. Treat the prediction and gold as a bag of tokens, and compute $\mathrm{F}{1},$ averaging the $\mathrm{F}_{1}$ over all questions.

26 Dialogue System and Chatbots

26.1 properties of Human Conversation

Turns: A dialogue is a sequence of turns (A1, B1, A2, and so on), each a single contribution to the dialogue (as if in a game: I take a turn, then you take a turn, then me, and so on).

Speech Acts: These actions are com- monly called speech acts or dialog acts: here’s one taxonomy consisting of 4 major classes.

![]()

Grounding: A dialogue is not just a series of independent speech acts, but rather a collective act performed by the speaker and the hearer. Speakers do this by grounding each other’s utterances. Ground- ing means acknowledging that the hearer has understood the speaker.

Subdialogues and Dialogue Structure: Conversations have structure. QUESTIONS set up an expectation for an ANSWER. PROPOSALS are followed by ACCEPTANCE (or REJECTION). COMPLIMENTS (“Nice jacket!”) often give rise to DOWNPLAYERS (“Oh, this old thing?”). These pairs, called adjacency pairs are composed of a first pair part and a second pair part.

Initiative: Sometimes a conversation is completely controlled by one participant. For example a reporter interviewing a chef might ask questions, and the chef responds. We say that the reporter in this case has the conversational initiative.

Inference and Implicature: The speaker seems to expect the hearer to draw certain inferences; in other words, the speaker is communicating more information than seems to be present in the uttered words.26.2 Chatbots

26.2.1 Rule-based chatbots: ELIZA and PARRY

26.2.2 Corpus-based chatbots

IR-based chatbots

return the response to the most similar turn:

\[r = response\left(\underset{t \in C}{\operatorname{argmax}} \frac{q^{T} t}{\|q\| t \|}\right)\]

Given user query $q$ and a conversational corpus $C,$ find the turn $t$ in $C$ that is most similar to $q$ (for example has the highest cosine with $q$ ) and return the following turn, i.e. the human response to $t$ in $C:$Return the most similar turn: Given user query $q$ and a conversational corpus $C,$ return the turn $t$ in $C$ that is most similar to $q$ (for example has the highest cosine with $q$ ):

\[r=\underset{t \in C}{\operatorname{argmax}} \frac{q^{T} t}{\|q\| t \|}\]Encoder decoder chatbots

Evaluating Chatbots

Word-overlap metrics like BLEU for comparing a chatbot’s response to a human response turn out to correlate very poorly with human judgments. BLEU performs poorly because there are so many possible responses to any given turn. word-overlap metrics work best when the space of responses is small and lexically overlapping, as is the case in machine translation.

Another paradigm is adversarial evaluation is to train a “Turing-like” evaluator classifier to distinguish between human-generated responses and machine-generated responses.

26.3 GUS: Simple Frame-based Dialogue Systems

- 26.3.1 Control structure for frame-based dialogue

- 26.3.2 Natural language understanding for filling slots in GUS

- 26.3.3 Other components of frame-based dialogue

26.4 The Dialogue-State Architecture

- 26.4.1 Dialogue Acts

- 26.4.2 Slot Filling

- 26.4.3 Dialogue State Tracking

- 26.4.4 Dialogue Policy

- 26.4.5 Natural language generation in the dialogue-state model

26.5 Evaluating Dialogue Systems

Task completion success:

Task success can be measured by evaluating the correctness of the total solution. For a frame-based architecture, this might be slot error rate the percentage of slots that were filled with the correct values.

Slot Error Rate for a Sentence $=\frac{# \text { of inserted/deleted/subsituted slots }}{# \text { of total reference slots for sentence }}$Efficient cost:

Can be measured by the total elapsed time for the dialogue in seconds, the number of total turns or of system turns, or the total number of queries.Quality cost:

One such measure is the number of times the ASR system failed to return any sentence, or the number of ASR rejection prompts. Similar metrics include the number of times the user had to barge in (interrupt the system), or the number of time-out prompts played when the user didn’t respond quickly enough.

26.6 Dialogue System Design

- Study the user and task

- Build simulations and prototypes

- Iteratively test the design on users