- Ⅰ Artificial Intelligence

- Ⅱ Problem-solving

- Ⅲ Knowledge, reasoning and planning

- Ⅳ Uncertain knowledge and reasoning

- Ⅴ Learning

- Ⅵ Communicating, perceiving and acting

- Ⅶ Conclusions

Ⅰ Artificial Intelligence

1 Introduction

- 1.1 What is AI:

- Thinking humanly

- Acting humanly

- Thinking nationally

Acting rationally

- 1.1.1 acting humanly: the turing test approach

- natural language processing

- knowledge representation

- automated reasoning

- machine learning

- computer vision

- robotics

1.1.2 thinking humanly: the cognitive modeling approach

The interdisciplinary field of cognitive science brings together computer models from AI and experimental techniques from psychology to construct precise and testable theories of the human mind.

1.1.3 thinking rationally: the “laws of thought” approach

There are two main obstacles to this approach. First, it is not easy to take informal knowledge and state it in the formal terms required by logical notation, particularly when the knowledge is less than 100% certain. Second, there is a big difference between solving a problem “in principle” and solving it in practice.

1.1.4 acting rationally: the rational agent approach

A rational agent is one that acts so as to achieve the best outcome or, when there is uncertainty, the best expected outcome.

- 1.2 The foundations of artificial intelligence

- 1.2.1 Philosophy

- 1.2.2 Mathematics

- 1.2.3 Economics

- 1.2.4 Neuroscience

- 1.2.5 Psychology

- 1.2.6 Computer engineering

- 1.2.7 Control theory and cybernetics

- 1.2.8 Linguistics

- 1.3 The history of artificial intelligence

1.3.1 The gestation of artificial intelligence (1943–1955)

Three resources:

- knowledge of the basic physiology and function of neurons in the brain

- a formal analysis of propositional logic due to Russell and Whitehead

- Turing’s theory of computation

- 1.3.2 The birth of artificial intelligence (1956)

- 1.3.3 Early enthusiasm, great expectations (1952–1969)

- 1.3.4 A dose of reality (1966–1973)

- 1.3.5 Knowledge-based systems: The key to power? (1969–1979)

- 1.3.6 AI becomes an industry (1980–present)

- 1.3.7 The return of neural networks (1986–present)

- 1.3.8 AI adopts the scientific method (1987–present)

- 1.3.9 The emergence of intelligent agents (1995–present)

- 1.3.10 The availability of very large data sets (2001–present)

- 1.4 The state of the art

- Robotic vehicles

- Speech recognition

- Autonomous planning and scheduling

- Game playing

- Spam fighting

- Logistics planning

- Robotics

- Machine Translation

2 Intelligent Agents

2.1 Agent and environments

An agent is anything that can be viewed as perceiving its environment through sensors and acting upon that environment through actuators.

2.2 Good behavior: the concept of rationality

A rational agent is one that does the right thing—conceptually speaking, every entry in the table for the agent function is filled out correctly. Definition: For each possible percept sequence, a rational agent should select an action that is expected to maximize its performance measure, given the evidence provided by the percept sequence and whatever built-in knowledge the agent has.

2.2.1 rationality

It’s depended on four things at any given time:

- The performance measure that defines the criterion of success

- The agent’s prior knowledge of the environment

- The actions that the agent can perform

- The agent’s percept sequence to date

2.2.2 omniscience, learning and autonomy

An omniscient agent knows the actual outcome of its actions and can act accordingly; but omniscience is impossible in reality

2.3 The nature of environments

2.3.1 specifying the task environment

PEAS (Performance, Environment, Actuators, Sensors)

2.3.2 Properties of task environments

- fully observable vs. partially

- single agent vs. multi-agent

- deterministic vs. stochastic

- episodic vs. sequential

- static vs. dynamic

- discrete vs. continuous

- known vs. unknown

As one might expect, the hardest case is partially observable, multi-agent, stochastic, sequential, dynamic, continuous, and unknown.

2.4 The structure of agents

2.4.1 agent programs

Four basic kinds of agent programs that embody the principles underlying almost all intelligent systems:

simple reflex agents:

These agents select actions on the basis of the current percept, ignoring the rest of the percept history.

model-based reflex agents:

The agent should maintain some sort of internal state that depends on the percept history and thereby reflects at least some of the unobserved aspects of the current state.

goal-based agents

The agent needs some sort of goal information that describes situations that are desirable.

utility-based agents

For example, many action sequences will get the taxi to its destination (thereby achieving the goal) but some are quicker, safer, more reliable, or cheaper than others. Because “happy” does not sound very scientific, economists and computer scientists use the term utility instead. Then an agent that chooses actions to maximize its utility will be rational according to the external performance measure.

2.4.6 learning agents

A learning agent can be divided into four conceptual components: learning element, performance element, critic, problem generator.

2.4.7 how the components of agent programs work

Roughly speaking, we can place the representations along an axis of increasing complexity and expressive power—atomic, factored, and structured.

In an atomic representation each state of the world is indivisible—it has no internal structure.

A factored representation splits up each state into a fixed set of variables or attributes, each of which can have a value.

Structured representation, in which objects such as cows and trucks and their various and varying relationships can be described explicitly.

Ⅱ Problem-solving

3 Solving problems by searching

3.1 Problem-solving agents

- 3.1.1 well-defined problems and solutions

- initial state

- actions

- transition model

- successor

- state space

- goal test: whether a given state is a goal state

- path cost

- 3.1.2 formulating problems

- 3.1.1 well-defined problems and solutions

3.2 Examples

- 3.3 Searching for solutions

- 3.3.1 infrastructure for search algorithms

- n.state: the state in the state space to which the node corresponds

- n.parent: the node in the search tree that generated this node

- n.action: the action that was applied to the parent to generate the node

- n.path-cost: the cost, traditionally denoted by g(n), of the path from the initial state to the node, as indicated by the parent pointers

FIFO queue; LIFO stack; priority queue

3.3.2 measuring problem-solving performance

Evaluating performance in four ways:

- Completeness: Is the algorithm guaranteed to find a solution when there is one?

- Optimality: Does the strategy find the optimal solution?

- Time complexity: How long does it take to find a solution?

- Space complexity: How much memory is needed to perform the search?

- 3.3.1 infrastructure for search algorithms

3.4 Uninformed search strategies

Uninformed search also called blind search.

- 3.4.1 breadth-first search (bfs): expanding the shallowest node

- 3.4.2 uniform-cost search: expands the node n with the lowest path cost g(n)

- 3.4.3 depth-first search (dfs): expands the deepest node in the current frontier of the search tree

- 3.4.4 depth-limited search: supplying depth-first search with a predetermined depth limit l. That is, nodes at depth l are treated as if they have no successors.

- 3.4.5 iterative deepening depth-first search: finds the best depth limit. It does this by gradually increasing the limit—first 0, then 1, then 2, and so on—until a goal is found. This will occur when the depth limit reaches d, the depth of the shallowest goal node.

- 3.4.6 bidirectional search: run two simultaneous searches—one forward from the initial state and the other backward from the goal—hoping that the two searches meet in the middle.

3.4.7 comparing uninformed search strategies

3.5 Informed (heuristic) search strategies

- evaluation function f(n): construed as a cost estimate

heuristic function h(n): estimated cost of the cheapest path from the state at node n to a goal state

- 3.5.1 greedy best-first search: expand the node that is closest to the goal. Thus, it evaluates nodes by using just the heuristic function; that is, f(n) = h(n).

- 3.5.2 A* search: minimizing the total estimated solution cost: It evaluates nodes by combining g(n), the cost to reach the node, and h(n), the cost to get from the node to the goal: f(n) = g(n) + h(n)

- 3.5.3 memory-bounded heuristic search: adapt the idea of iterative deepening to the heuristic search context, resulting in the iterative-deepening A∗ (IDA∗) algorithm.

- 3.6 Heuristic functions

- 3.6.1 the effect of heuristic accuracy on performance

- 3.6.2 generating admissible heuristics from relaxed problems

- 3.6.3 generating admissible heuristics from sub-problems: pattern databases

- 3.6.4 learning heuristics from experience

4 Beyond classical searching

4.1 Local search algorithms and optimization problems

local search algorithms operate using a single current node(rather than multiple paths) and generally move only to neighbors of that node.

It has two advantages: they use very little memory —- usually a constant amount; they can often find reasonable solutions in large or infinite (continuous) state spaces for which systematic algorithms are unsuitable.

4.1.1 hill-climbing search, so called greedy local search

It grabs a good neighbor state without thinking ahead about where to go next.

Unfortunately, hill climbing often gets stuck for the following reasons:

- local maxima

- ridges

- plateaux or shoulder

variants:

- stochastic hill climbing: chooses at random from among the uphill moves; the probability of selection can vary with the steepness of the uphill move.

- first-choice hill climbing: implements stochastic hill climbing by generating successors randomly until one is generated that is better than the current state.

- random-restart hill climbing: It con- ducts a series of hill-climbing searches from randomly generated initial states,1 until a goal is found.

4.1.2 simulated annealing

Combine hill climbing with a random walk in some way that yields both efficiency and completeness.

4.1.3 local beam search

Keeps track of k states rather than just one. It begins with k randomly generated states. At each step, all the successors of all k states are generated. If any one is a goal, the algorithm halts. Otherwise, it selects the k best successors from the complete list and repeats.

4.1.4 genetic algorithms

Genetic algorithm (or GA) is a variant of stochastic beam search. Successor states are generated by combining two parent states rather than by modifying a single state.

Like beam searches, GAs begin with a set of k randomly generated states, called the population. Each state, or individual, is represented as a string over a finite alphabet—most commonly, a string of 0s and 1s. Each state is rated by the objective function, or (in GA terminology) the fitness function. Two pairs are selected at random for reproduction. For each pair to be mated, a crossover point is chosen randomly from the positions in the string. Finally, each location is subject to random mutation with a small independent probability.

Like stochastic beam search, genetic algorithms combine an uphill tendency with ran- dom exploration and exchange of information among parallel search threads. The primary advantage, if any, of genetic algorithms comes from the crossover operation.

4.2 Local search in continuous spaces

- 4.3 Searching with nondeterministic actions

- 4.3.1 the erratic vacuum world

4.3.2 AND-OR search trees

In a deterministic environment, the only branching is introduced by the agent’s own choices in each state. We call these nodes OR nodes. In the vacuum world, for example, at an OR node the agent chooses Left or Right or Suck. In a nondeterministic environment, branching is also introduced by the environment’s choice of outcome for each action. We call these nodes AND nodes.

- 4.3.3 try, try again

4.4 Searching with partial observations

The key concept required for solving partially observable problems is the belief state, representing the agent’s current belief about the possible physical states it might be in, given the sequence of actions and percepts up to that point

- 4.4.1 searching with no observation

- belief states

- initial state

- actions

- transition model

- goal test

- path cost

- 4.4.2 searching with observation

- 4.4.3 solving partially observation problems

- 4.4.4 an agent for partially observable environment

- 4.4.1 searching with no observation

4.5 Online searching agents and unknown environments

Offline search algorithms. They compute a complete solution before setting foot in the real world and then execute the solution. In contrast, an online search13 agent interleaves computation and action. Online search is a necessary idea for unknown environments, where the agent does not know what state exist or what its actions do.

- 4.5.1 online search problems

- 4.5.2 online search agents

- 4.5.3 online local search

- 4.5.4 learning in online search

Ⅲ Knowledge, reasoning and planning

7 Logical agents

7.1 knowledge-based agents

A generic knowledge-based agent. Given a percept, the agent adds the percept to its knowledge base, asks the knowledge base for the best action, and tells the knowledge base that it has in fact taken that action.

Declarative approach to system building: knowledge-based agent can be built simply by TELLing it what it needs to know. Starting with an empty knowledge base, the agent designer can TELL sentences one by one until the agent knows how to operate in its environment.

Procedural approach to system building: encodes desired behaviors directly as program code.

- 7.2 The wumpus world

- Performance measure: +1000 for climbing out of the cave with the gold, –1000 for falling into a pit or being eaten by the wumpus, –1 for each action taken and –10 for using up the arrow. The game ends either when the agent dies or when the agent climbs out of the cave.

- Environment: A 4 × 4 grid of rooms.

- Actuators: The agent can move Forward, TurnLeft by 90 , or TurnRight by 90 .

- Sensors: The agent has five sensors, each of which gives a single bit of information:

- In the square containing the wumpus and in the directly (not diagonally) adjacent squares, the agent will perceive a Stench.

- In the squares directly adjacent to a pit, the agent will perceive a Breeze.

- In the square where the gold is, the agent will perceive a Glitter.

- When an agent walks into a wall, it will perceive a Bump.

- When the wumpus is killed, it emits a woeful Scream that can be perceived anywhere in the cave.

- 7.3 Logic

- 7.4 Propositional logic: a very simple logic

- 7.5 Propositional theorem proving

- 7.6 Effective propositional model checking

- 7.7 Agents based on propositional logic

8 First-order logic

- 8.1 Representation revisited

8.1.1 the language of thought

The modern view of natural language is that it serves a as a medium for communication rather than pure representation. Rather, the meaning of the sentence depends both on the sentence itself and on the context in which the sentence was spoken.

8.1.2 combining the best of formal and natural languages

- The syntax of natural language: object - people, houses, numbers, theories, Ronald McDonald, colors, baseball games, wars, centuries; relations - these can be unary relations or properties such as red, round, bogus, prime, multistoried…, or more general n-ary relations such as brother of, bigger than, inside, part of, has color, occurred after, owns, comes between; functions - father of, best friend, third inning of, one more than, beginning of.

The primary difference between propositional and first-order logic lies in the ontological commitment made by each language.

8.2 Syntax and semantics of first-order logic

8.2.1 models for first-order logic

Models for first-order logic are much more interesting. First, they have objects in them! The domain of a model is the set of objects or domain elements it contains.

The objects in the model may be related in various ways.

8.2.2 symbols and interpretations

- objects: constant symbols

- relations: predictive symbols

- functions: function symbols

One way to interpret: Each model includes an interpretation that specifies exactly which objects, relations and functions are referred to by the constant, predicate, and function symbols.

- 8.2.3 terms: A term is a logical expression that refers to an object

- 8.2.4 atomic sentences: combine both terms for referring to objects and predictive symbols for referring to relations, to make atomic sentence that state facts.

8.2.5 complex sentences: We can use logical connectives to construct more complex sentences, with the same syntax and semantics as in propositional calculus.

- 8.2.6 quantifiers

8.3 Using first-order logic

8.3.1 assertions and queries in first-order logic

Sentences are added to a knowledge base using TELL, exactly as in propositional logic. Such sentences are called assertions. For example, we have:

\[\begin{aligned} &\operatorname{TELL}(K B, \operatorname{King}(J o h n))\\ &\operatorname{TELL}(K B, \text { Person }(\text {Richard}))\\ &\operatorname{TELL}(K B, \forall x \quad \operatorname{King}(x) \Rightarrow \operatorname{Person}(x)) \end{aligned}\]We can ask questions of the knowledge base using ASK. For example:

\[\operatorname{Ask}(K B, \operatorname{King}(J o h n))\]If we want to know what value of x makes the sentence true, we will need a different function, ASKVARS, which we call with:

\[\operatorname{AsKVARS}(K B, P \operatorname{erson}(x))\]which yields a stream of answers. In this case there will be two answers: {x/John} and {x/Richard }. Such an answer is called a substitution or binding list.

8.3.2 the kinship domain

We can go through each function and predicate, writing down what we know in terms of the other symbols. For example, one’s mother is one’s female parent:

\[\forall m, c \quad \text {Mother}(c)=m \Leftrightarrow \text { Female }(m) \wedge \text { Parent }(m, c)\]8.3.3 numbers, sets, and lists

Numbers are perhaps the most vivid example of how a large theory can be built up from a tiny kernel of axioms. We describe here the theory of natural numbers or non-negative integers.

The Peano axioms define natural numbers and addition. Natural numbers are defined recursively:

\[\begin{aligned} &\text {NatNum(0).}\\ &\forall n \quad \text { NatNum }(n) \Rightarrow \text { NatNum }(S(n)) \end{aligned}\]The domain of sets is also fundamental to mathematics as well as to commonsense reasoning. The only sets are the empty set and those made by adjoining something to a set:

\[\forall s \quad \operatorname{Set}(s) \Leftrightarrow(s=\{\}) \vee\left(\exists x, s_{2} \quad \operatorname{Set}\left(s_{2}\right) \wedge s=\left\{x | s_{2}\right\}\right)\]Adjoining an element already in the set has no effect:

\[\forall x, s \quad x \in s \Leftrightarrow s=\{x | s\}\]Lists are similar to sets. The differences are that lists are ordered and the same element can appear more than once in a list.

8.3.4 the wumpus world

A typical percept sentence would be: Percept ([Stench, Breeze, Glitter, None, None], 5). Here, Percept is a binary predicate, and Stench and so on are constants placed in a list.

The actions in the wumpus world can be represented by logical terms:

\[\text { Turn(Right), Turn(Left), Forward, Shoot, Grab, Climb.}\]These rules exhibit a trivial form of the reasoning process called perception:

\[\begin{aligned} &\forall t, s, g, m, c \quad \text { Percept }([s, \text { Breeze, } g, m, c], t) \Rightarrow \text { Breeze(t)}\\ &\forall t, s, b, m, c \quad \text { Percept }([s, b, \text { Glitter, } m, c], t) \Rightarrow \text { Glitter }(t) \end{aligned}\]

8.4 Knowledge engineering in first-order logic

This section will illustrate the use of first-order logic to represent knowledge in three simple domains.

- 8.4.1 the knowledge-engineering process

- Identify the task

- Assemble the relevant knowledge

- Decide on a vocabulary of predicates, functions, and constants

- Encode general knowledge about the domain

- Encode a description of the specific problem instance

- Pose queries to the inference procedure and get answers

- Debug the knowledge base

- 8.4.1 the knowledge-engineering process

12 Knowledge representation

- 12.1 Ontological engineering

Ⅳ Uncertain knowledge and reasoning

13 Quantifying Uncertainty

13.1 Acting under uncertainty

Problem-solving agents and logical agents are designed to handle uncertainty by keeping track of a belief state - a representation of the set of all possible world states that is might be in.

However, this approach has significant drawbacks when taken literally as a recipe for creating agent programs:

- Leads to impossible large and complex belief-state representations

- Grow arbitrarily large and must consider arbitrarily unlikely contingencies.

- Sometimes there is no plan that is guaranteed to achieve the goal - yet the agent must act.

The agent’s knowledge cannot guarantee any of these outcomes for a specific action, but it can provide some degree of belief that they will be achieved. The right thing to do - the rational decision - therefore depends on both the relative importance of various goals and the likelihood that, and degree to which, whey will be achieved.

13.1.1 summarizing uncertainty

Take $\text { Cavity } \Rightarrow \text { Toothache }$ as a example to illustrate: The only way to fix the rule is to make it logically exhaustive: to augment the left-hand side with all the qualifications required for a cavity to cause a toothache. Trying to use logic to cope with a domain like medical diagnosis thus fails for three main reasons:

- laziness: It is too much work to list the complete set of antecedents or consequents needed to ensure an exceptionless rule and too hard to use such rules.

- theoretical ignorance: Medical science has no complete theory for the domain.

- practical ignorance: Even if we know all the rules, we might be uncertain about a particular patient because not all the necessary tests have been or can be run.

Probability provides a way of summarizing the uncertainty that comes from our laziness and ignorance, thereby solving the qualification problem.

13.1.2 uncertainty and rational decisions

Agent must first have preference between the different possible outcomes of the various plans. We use utility theory to represent and reason with preferences. Utility theory says that every state has a degree of usefulness, or utility, to an agent and that the agent will prefer states with higher utility.

Preference, as expressed by utility, are combined with probabilities in the general theory of rational decisions called decision theory:

\[\text { Decision theory }=\text { probability theory + utility theory. }\]An agent is rational if and only if it chooses the action that yields the highest expected utility, averaged over all the possible outcomes of the action. This is called the principle of maximum expected utility (MEU).

13.2 Basic Probability Notation

13.2.1 what probabilities are about

In probability theory, the set of all possible worlds is called the sample space. Let’s take rolling dice as example. A fully specified probability model associates a numerical probability P (ω) with each possible world. The basic axioms of probability theory say that every possible world has a probability between 0 and 1 and that the total probability of the set of possible worlds is 1:

\[0 \leq P(\omega) \leq 1 \text { for every } \omega \text { and } \sum_{\omega \in \Omega} P(\omega)=1\]For example, we might interested in the cases where two dice add up to 11, all the sets are always described by propositions in a formal language. For each proposition, the corresponding set contains just those possible worlds in which the proposition holds.

\[\text { For any proposition } \phi, P(\phi)=\sum_{\omega \in \phi} P(\omega)\]Probabilities such as P (Total = 11) and P (doubles) are called unconditional or prior probabilities.

Most of the time, however, we have some information, usually called evidence, that has already been revealed(e.g. first die is 5). In that case, we are interested not in the unconditional probability of rolling doubles, but the conditional or posterior probability (or just “posterior” for short) of rolling doubles given that the first die is a 5. This probability is written as: $P\left(\text { doubles } \text { Die}_{1}=5\right)$. the $ $ is pronounced “given”. Mathematically speaking, conditional probabilities are defined in terms of unconditional probabilities as follows: for any propositions a and b, we have:

\[P(a | b)=\frac{P(a \wedge b)}{P(b)}\]13.2.2 the language of propositions in probability assertions

Variables in probability theory are called random variables and their names begin with an uppercase letter.

Every random variable has a domain—the set of possible values it can take on. The domain of Total for two dice is the set {2,…,12} and the domain of Die1 is {1,…,6}. For example:

\[\begin{array}{l}{P(\text { Weather }=\operatorname{sunn} y)=0.6} \\ {P(\text {Weather}=\operatorname{rain})=0.1} \\ {P(\text {Weather}=\text {cloudy})=0.29} \\ {P(\text {Weather}=\text {snow})=0.01}\end{array}\]but as an abbreviation we will allow:

\[\mathbf{P}(\text {Weather})=\langle 0.6,0.1,0.29,0.01\rangle\]For continuous variables, it is not possible to write out the entire distribution as a vector, because there are infinitely many values. Instead, we can define the probability that a random variable takes on some value x as a parameterized function of x. For example, the sentence:

\[P(\text {Noon Temp}=x)=\text {Uniform}_{[18 C, 26 C]}(x)\]expresses the belief that the temperature at noon is distributed uniformly between 18 and 26 degrees Celsius. We call this a probability density function.

Saying that the probability density is uniform from 18C to 26C means that there is a 100% chance that the temperature will fall somewhere in that 8C-wide region and a 50% chance that it will fall in any 4C-wide region, and so on.

The intuitive definition of P (x) is the probability that X falls within an arbitrarily small region beginning at x, divided by the width of the region:

\[P(x)=\lim _{d x \rightarrow 0} P(x \leq X \leq x+d x) / d x\]It is not a probability, it is a probability density.

In addition to distributions on single variables, we need notation for distributions on multiple variables.

P(Weather,Cavity) denotes the probabilities of all combinations of the values of Weather and Cavity. This is a 4×2 table of probabilities called the joint probability distribution of Weather and Cavity.

\[\mathbf{P}(\text {Weather}, \text { Cavity })=\mathbf{P}(\text { Weather } | \text { Cavity }) \mathbf{P}(\text { Cavity })\]From the preceding definition of possible worlds, it follows that a probability model is completely determined by the joint distribution for all of the random variables—the so-called full joint probability distribution. For example, if the variables are Cavity, Toothache, and Weather, then the full joint distribution is given by P(Cavity,Toothache,Weather). This joint distribution can be represented as a 2 × 2 × 4 table with 16 entries.

13.2.3 probability axioms and their reasonableness

inclusion–exclusion principle:

\[P(a \vee b)=P(a)+P(b)-P(a \wedge b)\]If Agent 1 expresses a set of degrees of belief that violate the axioms of probability theory then there is a combination of bets by Agent 2 that guarantees that Agent 1 will lose money every time. De Finetti’s theorem implies that no rational agent can have beliefs that violate the axioms of probability:

13.3 INference Using Full joint Distributions

We begin with a simple example: a domain consisting of just the three Boolean variables Toothache, Cavity, and Catch (the dentist’s nasty steel probe catches in my tooth). The full joint distribution is a 2 × 2 × 2 table as shown below:

One particularly common task is to extract the distribution over some subset of variables or a single variable. For example, adding the entries in the first row gives the unconditional or marginal probability4 of cavity:

\[P(\text { cavity })=0.108+0.012+0.072+0.008=0.2\]This process is called marginalization, or summing out. We can write the following general marginalization rule for any sets of variables Y and Z:

\[\mathbf{P}(\mathbf{Y})=\sum_{\mathbf{z} \in \mathbf{Z}} \mathbf{P}(\mathbf{Y}, \mathbf{z})\]A variant of this rule involves conditional probabilities instead of joint probabilities, using the product rule:

\[\mathbf{P}(\mathbf{Y})=\sum_{\mathbf{z}} \mathbf{P}(\mathbf{Y} | \mathbf{z}) P(\mathbf{z})\]\[\mathbf{P}(X | \mathbf{e})=\alpha \mathbf{P}(X, \mathbf{e})=\alpha \sum_{\mathbf{y}} \mathbf{P}(X, \mathbf{e}, \mathbf{y})\] \[\begin{aligned} P(\text { cavity } | \text { toothache }) &=\frac{P(\text { cavity } \wedge \text { toothache })}{P(\text { toothache })} \\ &=\frac{0.108+0.012}{0.108+0.012+0.016+0.064}=0.6 \end{aligned}\] \[\begin{aligned} P(\neg cavity | \text {toothache}) &=\frac{P({ \neg cavity } \wedge \text {toothache})}{P(\text {toothache})} \\ &=\frac{0.016+0.064}{0.108+0.012+0.016+0.064}=0.4 \end{aligned}\] \[\begin{array}{l}{\mathbf{P}(\text {Cavity } | \text {toothache})=\alpha \mathbf{P}(\text {Cavity, toothache})} \\ {=\alpha[\mathbf{P}(\text {Cavity, toothache, catch})+\mathbf{P}(\text {Cavity,toothache}, { \neg catch })]} \\ {=\alpha[\langle 0.108,0.016\rangle+\langle 0.012,0.064\rangle]=\alpha\langle 0.12,0.08\rangle=\langle 0.6,0.4\rangle}\end{array}\]From the example, we can extract a general inference procedure. We begin with the case in which the query involves a single variable, X (Cavity in the example). Let E be the list of evidence variables (just Toothache in the example), let e be the list of observed values for them, and let Y be the remaining unobserved variables (just Catch in the example). The query is P(X e) and can be evaluated as: 13.4 Independence

The property we used in Equation (13.10) is called independence (also marginal in- dependence and absolute independence). Can be written as:

\[P(a | b)=P(a) \quad \text { or } \quad P(b | a)=P(b) \quad \text { or } \quad P(a \wedge b)=P(a) P(b)\] \[\mathbf{P}(X | Y)=\mathbf{P}(X) \quad \text { or } \quad \mathbf{P}(Y | X)=\mathbf{P}(Y) \quad \text { or } \quad \mathbf{P}(X, Y)=\mathbf{P}(X) \mathbf{P}(Y)\]13.5 Bayes’ Rule and its Use

\[P(b | a)=\frac{P(a | b) P(b)}{P(a)}\] \[\mathbf{P}(Y | X)=\frac{\mathbf{P}(X | Y) \mathbf{P}(Y)}{\mathbf{P}(X)}\]We will also have occasion to use a more general version conditionalized on some background evidence e:

\[\mathbf{P}(Y | X, \mathbf{e})=\frac{\mathbf{P}(X | Y, \mathbf{e}) \mathbf{P}(Y | \mathbf{e})}{\mathbf{P}(X | \mathbf{e})}\]13.5.1 applying bayes’ rule: the simple case

\[\begin{aligned} P(s | m) &=0.7 \\ P(m) &=1 / 50000 \\ P(s) &=0.01 \\ P(m | s) &=\frac{P(s | m) P(m)}{P(s)}=\frac{0.7 \times 1 / 50000}{0.01}=0.0014 \end{aligned}\]Instead computing a posterior probability for each value of the quey variable and then normalizing the results. The same process can be applied when using Bayes’ rule. We have:

\[\mathbf{P}(M | s)=\alpha\langle P(s | m) P(m), P(s | \neg m) P(\neg m)\rangle\]13.5.2 using bayes’ rule: combining evidence

As above section said, regard it as normalization we have:

\[\begin{array}{l}{\mathbf{P}(\text {Cavity} | \text {toothache } \wedge \text {catch})} \\ {\quad=\alpha \mathbf{P}(\text {toothache} \wedge \text {catch} | \text {Cavity}) \mathbf{P}(\text {Cavity})}\end{array}\]It would be nice if Toothache and Catch were independent, but they are not: if the probe catches in the tooth, then it is likely that the tooth has a cavity and that the cavity causes a toothache. These variables are independent, however, given the presence or the absence of a cavity.

\[\mathbf{P}(\text {toothache} \wedge \text { catch } | \text { Cavity })=\mathbf{P}(\text { toothache } | \text { Cavity) } \mathbf{P}(\text { catch } | \text { Cavity })\]This equation expresses the conditional independence of toothache and catch given Cavity.

\[\begin{array}{l}{\mathbf{P}(\text { Cavity } | \text { toothache } \wedge \text { catch })} \\ {\quad=\alpha \mathbf{P}(\text { toothache } | \text { Cavity }) \mathbf{P}(\text { catch } | \text { Cavity }) \mathbf{P}(\text { Cavity })}\end{array}\]The general definition of conditional independence of two variables X and Y , given a third variable Z, is:

\[\mathbf{P}(X, Y | Z)=\mathbf{P}(X | Z) \mathbf{P}(Y | Z)\]The equivalent forms(X and Y are independent to each other):

\[\mathbf{P}(X | Y, Z)=\mathbf{P}(X | Z) \quad \text { and } \quad \mathbf{P}(Y | X, Z)=\mathbf{P}(Y | Z)\]So finally we can derive a decomposition as follows:

\[\begin{array}{l}{\mathbf{P}( \text {Toothache, Catch,Cavity)} } \\ {=\mathbf{P}(\text {Toothache}, \text {Catch} | \text {Cavity}) \mathbf{P}(\text {Cavity}) \text { (product rule) }} \\ {=\mathbf{P}(\text {Toothache} | \text {Cavity}) \mathbf{P}(\text {Catch} | \text {Cavity}) \mathbf{P}(\text {Cavity}) )}\end{array}\]The dentistry example illustrates a commonly occurring pattern in which a single cause directly influences a number of effects, all of which are conditionally independent, given the cause. The full joint distribution can be written as:

\[\mathbf{P}\left(\text {Cause }, \text {Effect}_{1}, \ldots, \text { Effect }_{n}\right)=\mathbf{P}(\text { Cause }) \prod_{i} \mathbf{P}\left(\text {Effect}_{i} | \text { Cause }\right)\]

14 Probabilistic Reasoning

14.1 Representing Knowledge In An Uncertain Domain

we saw that the full joint probability distribution can answer any question about the domain, but can become intractably large as the number of variables grows. Furthermore, specifying probabilities for possible worlds one by one is unnatural and tedious.

This section introduces a data structure called a Bayesian network1 to represent the dependencies among variables.

Bayesian network full specification is as follows:

- Each node corresponds to a random variable, which may be discrete or continuous.

- A set of directed links or arrows connects pairs of nodes. If there is an arrow from node X to node Y , X is said to be a parent of Y. The graph has no directed cycles (and hence is a directed acyclic graph, or DAG.

Each node $X_i$ has a conditional probability distribution $P(X_i Parents(X_i))$ that quantifies the effect of the parents on the node.

The network structure shows that burglary and earthquakes directly affect the probability of the alarm’s going off, but whether John and Mary call depends only on the alarm. The network thus represents our assumptions that they do not perceive burglaries directly, they do not notice minor earth- quakes, and they do not confer before calling.

14.2 The Semantics of Bayesian Networks

14.2.1 Representing the full joint distribution

A generic entry in the joint distribution is the probability of a conjunction of particular assignments to each variable, such as $P\left(X_{1}=x_{1} \wedge \ldots \wedge X_{n}=x_{n}\right)$ We use the notation $P\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{n}\right)$ as an abbreviation for this. The value of this entry is given by the formula:

\[P\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{n}\right)=\prod^{n} \theta\left(x_{i} | \text { parents }\left(X_{i}\right)\right)\]Thus, each entry in the joint distribution is represented by the product of the appropriate elements of the conditional probability tables (CPTs) in the Bayesian network.

\[P\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{n}\right)=\prod_{n} P\left(x_{i} | \text { parents }\left(X_{i}\right)\right)\]From this definition, it is easy to prove that the parameters $\theta\left(X_{i} \text { Parents }\left(X_{i}\right)\right)$ are exactly the conditional probabilities $\mathbf{P}\left(X_{i} \text { Parents }\left(X_{i}\right)\right)$ implied by the joint distribution (see Exercise 14.2 ). Hence, we can rewrite Equation ( 14.1) as Fro example, the alarm has sounded, but neither a burglary nor an earthquake has occurred, and both John and Mary call:

\[\begin{aligned} P(j, m, a, \neg b, \neg e) &=P(j | a) P(m | a) P(a | \neg b \wedge \neg e) P(\neg b) P(\neg e) \\ &=0.90 \times 0.70 \times 0.001 \times 0.999 \times 0.998=0.000628 \end{aligned}\]A method for constructing Bayesian networks

We have:

\[P\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{n}\right)=P\left(x_{n} | x_{n-1}, \ldots, x_{1}\right) P\left(x_{n-1}, \ldots, x_{1}\right)\]Then we repeat the process, reducing each conjunctive probability to a conditional probability and a smaller conjunction. We end up with one big product:

\[\begin{aligned} P\left(x_{1}, \ldots, x_{n}\right) &=P\left(x_{n} | x_{n-1}, \ldots, x_{1}\right) P\left(x_{n-1} | x_{n-2}, \ldots, x_{1}\right) \cdots P\left(x_{2} | x_{1}\right) P\left(x_{1}\right) \\ &=\prod_{i=1}^{n} P\left(x_{i} | x_{i-1}, \ldots, x_{1}\right) \end{aligned}\]Compactness and node ordering

The compactness of Bayesian net- works is an example of a general property of locally structured (also called sparse) systems.

In the case of Bayesian networks, it is reasonable to suppose that in most domains each random variable is directly influenced by at most k others, for some constant k.

There are domains in which each variable can be influenced directly by all the others, so that the network is fully connected.

Whether to add the link from Earthquake to JohnCalls and MaryCalls (and thus enlarge the tables) depends on comparing the importance of getting more accurate probabilities with the cost of specifying the extra information.

Suppose we decide to add the nodes in the order MaryCalls, JohnCalls, Alarm, Burglary, Earthquake. We then get the somewhat more complicated network shown in Figure 14.3(a).

Figure 14.3(b) shows a very bad node ordering: MaryCalls, JohnCalls, Earthquake, Burglary, Alarm.

14.2.2 conditional independence relations in Bayesian networks

14.3 Efficient representation of Conditional Distributions

from this information and the noisy-OR assumptions, the entire CPT can be built. The general rule is that:

\[P\left(x_{i} | \text { parents }\left(X_{i}\right)\right)=1-\prod_{\left\{j: X_{j}=true\right\}.} q_{j}\]Bayesian nets with continuous variables

it is impossible to specify conditional probabilities explicitly for each value. One possible way to handle continuous variables is to avoid them by using discretization.

A network with both discrete and continuous variables is called a hybrid Bayesian network.

We specify the parameters of the cost distribution as a function of h. The most common choice is the linear Gaussian distribution, in which the child has a Gaussian distribution whose mean μ varies linearly with the value of the parent and whose standard deviation σ is fixed. We need two distributions, one for subsidy and one for ¬subsidy, with different parameters:

\[\begin{array}{c} {P(c | h, s u b s i d y)=N\left(a_{t} h+b_{t}, \sigma_{t}^{2}\right)(c)=\frac{1}{\sigma_{t} \sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{-\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{c-\left(a_{t} h+b_{t}\right)}{\sigma_{t}}\right)^{2}}} \\ {P(c | h, \neg s u b s i d y)=N\left(a_{f} h+b_{f}, \sigma_{f}^{2}\right)(c)=\frac{1}{\sigma_{f} \sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{-\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{c-\left(a_{f} h+b_{f}\right)}{\sigma_{f}}\right)^{2}}} \end{array}\]For this example, then, the conditional distribution for Cost is specified by naming the linear Gaussian distribution and providing the parameters $a_{t}, b_{t}, \sigma_{t}, a_{f}, b_{f},$ and $\sigma_{f} .$

14.4 Exact Inference in Bayesian Networks

The basic task for any probabilistic inference system is to compute the posterior probability distribution for a set of query variables, given some observed event.

$X$ denotes the query variable;

$E$ denotes the set of evidence variables $E_1 , . . . , E_m$, and

$e$ is a particular observed event;

$Y$ will denotes the nonevidence, nonquery variables $Y_1, . . . , Y_l$(called the hidden variables).14.4.1 Inference by enumeration

\[\mathbf{P}(X | \mathbf{e})=\alpha \mathbf{P}(X, \mathbf{e})=\alpha \sum_{y} \mathbf{P}(X, \mathbf{e}, \mathbf{y})\]More specifically, a query P(X e) can be answered using Equation (13.9), which we repeat here for convenience: \[\mathbf{P}(B | j, m)=\alpha \mathbf{P}(B, j, m)=\alpha \sum_{e} \sum_{a} \mathbf{P}(B, j, m, e, a,)\] \[P(b | j, m)=\alpha \sum_{e} \sum_{a} P(b) P(e) P(a | b, e) P(j | a) P(m | a)\]Consider the query (\mathbf{P}(\text {Burglary} \text {JohnCalls}=\text {true}, \text {MaryCalls}=\text {true}) .) The hidden variables for this query are Earthquake and Alarm. From Equation ((13.9),) using initial letters for the variables to shorten the expressions, we have (^{4}) An improvement can be obtained from the following simple observations: the P(b) term is a constant and can be moved outside the summations over a and e, and the P (e) term can be moved outside the summation over a.

\[P(b | j, m)=\alpha P(b) \sum_{e} P(e) \sum_{a} P(a | b, e) P(j | a) P(m | a)\]14.4.2 The variable elimination algorithm

14.4.3 the complexity of exact inference

14.4.4 Clustering algorithms

14.5 Approximate Inference in Bayesian Networks

14.5.1 Direct sampling methods

- Rejection sampling in Bayesian networks

- Likelihood weighting

14.5.2 Inference by Markov chain simulation

- Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)

- Gibbs sampling in Bayesian networks

- Why Gibbs sampling works

14.7 Other Approaches to Uncertain Reasoning

- 14.7.1 Rule-based mthods for uncertain reasoning

- Locality

- Detachment

- Truth-functionality

- 14.7.2 Representing ignorance: Dempster-Shafer theory

- 14.7.3 Representing vagueness: Fuzzy sets and fuzzy logic

- 14.7.1 Rule-based mthods for uncertain reasoning

15 Probabilistic Reasoning over Time

15.1 Time and Uncertainty

Now consider a slightly different problem: treating a diabetic patient. We have evidence such as recent insulin doses, food intake, blood sugar measurements, and other physical signs. The task is to assess the current state of the patient, including the actual blood sugar level and insulin level. To assess the current state from the history of evidence and to predict the outcomes of treatment actions, we must model these changes.

15.1.1 states and observations

We view the world as a series of snapshots, or time slices, each of which contains a set of random variables, some observable and some not.

We will use $X_t$ to denote the set of state variables at time $t$, which are assumed to be unobservable, and $E_t$ to denote the set of observable evidence variables. The observation at time $t$ is $E_t = e_t$ for some set of values $e_t$.

The interval between time slices also depends on the problem. In this chapter we assume the interval between slices is fixed, so we can label times by integers. We will assume that the state sequence starts at t = 0.

15.1.2 transition and sensor models

With the set of state and evidence variables for a given problem decided on, the next step is to specify how the world evolves (the transition model) and how the evidence variables get their values (the sensor model).

The transition model specifies the probability distribution over the latest state variables, given the previous values, that is $\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t} \mathbf{X}_{0: t-1}\right)$. Markov assumption: that the current state depends on only a finite fixed number of previous states.

They come in various flavors; the simplest is the first-order Markov process, in which the current state depends only on the previous state and not on any earlier states. So we have a simplified form:

\[\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t} | \mathbf{X}_{0: t-1}\right)=\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t} | \mathbf{X}_{t-1}\right)\]Similar to previous, second-order Markov process is:

\[\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t} | \mathbf{X}_{t-2}, \mathbf{X}_{t-1}\right)\]Even with the Markov assumption there is still a problem: there are infinitely many possible values of t.

Solution: We avoid this problem by assuming that changes in the world state are caused by a stationary process. In the umbrella world, then, the conditional probability of rain, $P(R_t R_t−1)$, is the same for all $t$, and we only have to specify one conditional probability table. Now for the sensor model. The evidence variables $E_t$ could depend on previous variables as well as the current state variables($E$ is umbrella). Thus, we make a sensor Markov assumption as follows:

\[\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{E}_{t} | \mathbf{X}_{0: t}, \mathbf{E}_{0: t-1}\right)=\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{E}_{t} | \mathbf{X}_{t}\right)\]Thus, $P(E_t X_t)$ is our sensor model (sometimes called the observation model). In addition to specifying the transition and sensor models, we need to say how every- thing gets started—the prior probability distribution at time 0, $P(X_0)$.

With that, we have a specification of the complete joint distribution over all the variables:

\[\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{0: t}, \mathbf{E}_{1: t}\right)=\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{0}\right) \prod_{i=1}^{t} \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{i} | \mathbf{X}_{i-1}\right) \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{E}_{i} | \mathbf{X}_{i}\right)\]The three terms on the right-hand side are the initial state model $P(X_0)$, the transition model $P(X_i X_{i−1})$, and the sensor model P(E_i X_i). Two ways to improve the accuracy of the approximation:

- Increasing the order of the Markov process model

- Increasing the set of state variables

15.2 Inference in Temporal Models

Filtering: This is the task of computing the belief state — the posterior distribution over the most recent state—given all evidence to date. In our example, we wish to compute $\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t} \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right)$. Prediction: This is the task of computing the posterior distribution over the future state, given all evidence to date. That is, we wish to compute $\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+k} \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right) \text { for some } k>0$ Smoothing: This is the task of computing the posterior distribution over a past state, given all evidence up to the present. That is, we wish to compute $\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{k} \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right)$ for some $k$ such that $0 \leq k \le t$ Most likely explanation: Given a sequence of observations, we might wish to find the sequence of states that is most likely to have generated those observations. That is, we wish to compute $\operatorname{argmax}{\mathbf{x}{1: t}} P\left(\mathbf{x}_{1: t} \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right)$ - Learning: The transition and sensor models, if not yet known, can be learned from observations. Inference provides an estimate of what transitions actually occurred and of what states generated the sensor readings, and these estimates can be used to update the models. The updated models provide new estimates, and the process iterates to convergence. The overall process is an instance of the expectation- maximization or EM algorithm.

15.2.1 filtering and prediction

Given the result of filtering up to time t, the agent needs to compute the result for t + 1 from the new evidence $e_{t+1}$:

\[\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+1} | \mathbf{e}_{1: t+1}\right)=f\left(\mathbf{e}_{t+1}, \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t} | \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right)\right)\]This process is called recursive estimation. We can view the calculation as being composed of two parts: first, the current state distribution is projected forward from t to t+1; then it is updated using the new evidence $e_{t+1}$. This two-part process emerges quite simply when the formula is rearranged:

\[\begin{array}{l} {\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+1} | \mathbf{e}_{1: t+1}\right)=\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+1} | \mathbf{e}_{1: t}, \mathbf{e}_{t+1}\right) \text { (dividing up the evidence) }} \\ {=\alpha \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{e}_{t+1} | \mathbf{X}_{t+1}, \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right) \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+1} | \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right) \text { (using Bayes' rule) }} \\ {=\alpha \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{e}_{t+1} | \mathbf{X}_{t+1}\right) \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+1} | \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right) \quad \text { (by the sensor Markov assumption) }} \end{array}\]Where $\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{e}_{t+1} \mathbf{X}{t+1}, \mathbf{e}{1: t}\right) \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+1} \mathbf{e}{1: t}\right)$ equals to $\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}{t+1}, \mathbf{e}{1: t}, \mathbf{e}{t+1}\right)$ $\alpha$ is a normalizing constant used to make probabilities sum up to 1. The second term, $\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+1} \mathbf{e}{1: t}\right)$ represents a one-step prediction of the next state. The first term updates this with the new evidence; notice that $\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{e}{t+1} \mathbf{X}_{t+1}\right)$ is obtainable directly from the sensor model. Now we obtain the one-step prediction for the next state by conditioning on the current state $X_t$:

\[\begin{array}{l} {\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+1} | \mathbf{e}_{1: t+1}\right)=\alpha \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{e}_{t+1} | \mathbf{X}_{t+1}\right) \sum_{\mathbf{x}_{t}} \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+1} | \mathbf{x}_{t}, \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right) P\left(\mathbf{x}_{t} | \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right)} \\ {=\alpha \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{e}_{t+1} | \mathbf{X}_{t+1}\right) \sum_{\mathbf{x}_{t}} \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+1} | \mathbf{x}_{t}\right) P\left(\mathbf{x}_{t} | \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right) \quad \text { (Markov assumption) }} \end{array}\]Hence, we have the desired recursive formulation.

\[\mathbf{f}_{1: t+1}=\alpha \operatorname{FORWARD}\left(\mathbf{f}_{1: t}, \mathbf{e}_{t+1}\right)\]It is easy to derive the following recursive computation for predicting the state at t + k + 1 from a prediction for t + k:

\[\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+k+1} | \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right)=\sum_{\mathbf{x}_{t+k}} \mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}_{t+k+1} | \mathbf{x}_{t+k}\right) P\left(\mathbf{x}_{t+k} | \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right)\]In addition to filtering and prediction, we can use a forward recursion to compute the likelihood of the evidence sequence, $P\left(\mathbf{e}{1: t}\right)$. This is a useful quantity if we want to compare different temporal models that might have produced the same evidence sequence (e.g., two different models for the persistence of rain). For this recursion, we use a likelihood message $\ell{1: t}\left(\mathbf{X}{t}\right)=\mathbf{P}\left(\mathbf{X}{t}, \mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right)$. It is a simple exercise to show that the message calculation is identical to that for filtering:

\[\ell_{1: t+1}=\text { FORWARD }\left(\ell_{1: t}, \mathbf{e}_{t+1}\right)\]Having computed $\ell_{1: t}$, we obtain the actual likelihood by summing out $\mathbf{X_t}$:

\[L_{1: t}=P\left(\mathbf{e}_{1: t}\right)=\sum_{\mathbf{x}_{t}} \ell_{1: t}\left(\mathbf{x}_{t}\right)\]- 15.2.2 smoothing

- 15.2.3 finding the most likely sequence

15.3 Hidden Markov Models

We begin with the hidden Markov model, or HMM. An HMM is a temporal probabilistic model in which the state of the process is described by a single discrete random variable.

15.3.1 simplified matrix algorithms

\[\mathbf{T}_{i j}=P\left(X_{t}=j | X_{t-1}=i\right)\]Let the state variable Xt have values denoted by integers 1, . . . , S, where S is the number of possible states. The transition model $P(X_t X_{t−1})$ becomes an S × S matrix T, where: For example, the transition matrix for the umbrella world is:

\[\mathbf{T}=\mathbf{P}\left(X_{t} | X_{t-1}\right)=\begin{array}{cc} {0.7} & {0.3} \\ {0.3} & {0.7} \end{array}\]\[\mathbf{O}_{1}=\left(\begin{array}{cc} {0.9} & {0} \\ {0} & {0.2} \end{array}\right) ; \quad \mathbf{O}_{3}=\left(\begin{array}{cc} {0.1} & {0} \\ {0} & {0.8} \end{array}\right)\]because the value of the evidence variable Et is known at time t (call it et), we need only specify, for each state, how likely it is that the state causes et to appear: we need $P (e_t X_t = i)$ for each state i. $\mathbf{O}_{t}$ whose $i$th diagonal entry is $P (e_t X_t = i)$ and whose other entries are 0.For example, on day 1 in the umbrella world of Figure 15.5, U1 = true , and on day 3, U3 = false , so, from Figure 15.2, we have: Then the forward equation becomes:

\[\mathbf{f}_{1: t+1}=\alpha \mathbf{O}_{t+1} \mathbf{T}^{\top} \mathbf{f}_{1: t}\]backward equation becomes:

\[\mathbf{b}_{k+1: t}=\mathbf{T} \mathbf{O}_{k+1} \mathbf{b}_{k+2: t}\]Let’s go through a example to illustrate it. Suppose we have these balls below:

Ball A B C D #red ball 5 3 6 8 #white ball 5 7 4 2 Then, we pick 5 balls from those boxes with replacement, the first box we select is randomly from those five boxes with uniform probability, after the first box we follow a specific pattern to choose the next box. Finally we have $O = \left{ Red,\ Red,\ White,\ Red,\ White \right}$, but we don’t know what box we choose to pick from every time, e.g. $B = \left{ \text{box}?,\ \text{box}?,\ \text{box}?,\ \text{box}?,\ \text{box}? \right}$, we call it hidden state. So, the $O$ sequence is the observation sequence that we can observe directly, $B$ sequence is the state sequence that we cannot observe. Both of them have length of 5.

\[A = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0.4 & 0 & 0.6 & 0 \\ 0 & 0.4 & 0 & 0.6 \\ 0 & 0 & 0.5 & 0.5 \\ \end{bmatrix}\] \[a_{\text{ij}}\ \text{represents\ }\text{the\ probablity\ to\ select\ bo}x_{j}\text{\ if\ current\ is\ bo}x_{i}\]

So, why we put the example above here? The selecting box process is a state transition, because the next box we select is depends on previous box. E.g. If current box is A, we have 100% chance to select box B as next box. If current box is C, we have 40% chance to select box B as next box, 60% chance for box D. We can use a state transition matrix to represent the probabilities.Also, according to table 1, we can produce a matrix that represents the probability of ball color we pick given a particular box.

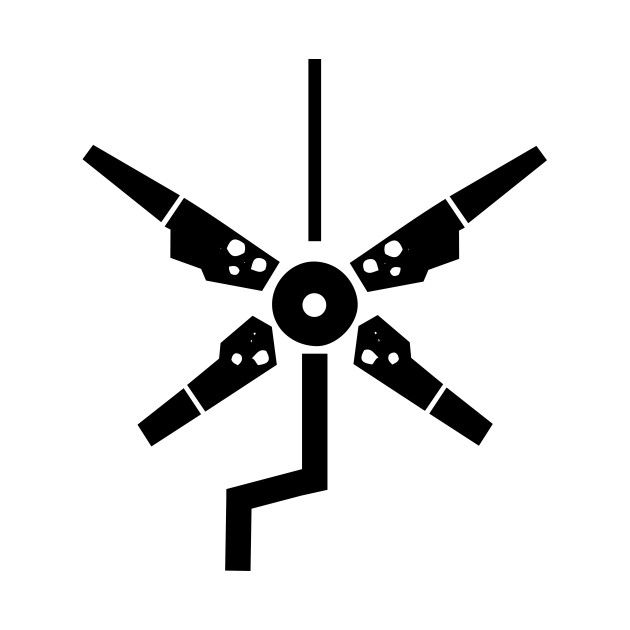

\[B = \begin{bmatrix} 0.5 & 0.5 \\ 0.3 & 0.7 \\ 0.6 & 0.4 \\ 0.8 & 0.2 \\ \end{bmatrix}\] \[b_{\text{ij}}\text{\ represents\ the\ probability\ of\ picking\ ball\ with\ colo}r_{i},\text{\ given\ bo}x_{i}\]These two matrices are the key idea of HMM, matrix $A$ tells us how state evolve over time, matrix $B$ tells us the probability of what we observed given that hidden state. We can use a chain figure to represent the relationship as figure 1 shows.

Figure 1. Relationship between state sequence and observe sequence[^1]

\[{P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle| e_{1:t + 1} \right) = P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle| e_{1:t},\ e_{t + 1} \right) = \frac{P\left( X_{t + 1},e_{1:t},e_{t + 1} \right)}{P\left( e_{1:t},\ e_{t + 1} \right)} }{= \frac{P\left( e_{t + 1}|X_{t + 1},e_{1:t} \right) \cdot P\left( X_{t + 1},e_{1:t} \right)}{P\left( e_{1:t},\ e_{t + 1} \right)} }{= \frac{P\left( e_{t + 1}|X_{t + 1},e_{1:t} \right) \cdot P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle| e_{1:t} \right) \cdot P\left( e_{1:t} \right)}{P\left( e_{t + 1} \middle| e_{1:t} \right) \cdot P\left( e_{1:t} \right)} }{= \alpha \cdot P\left( e_{t + 1}|X_{t + 1},e_{1:t} \right) \cdot P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle| e_{1:t} \right) }{= \alpha \cdot P\left( e_{t + 1}|X_{t + 1} \right) \cdot P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle| e_{1:t} \right)}\]After illustrating the idea of HMM, let’s talk about the inference using HMM. Here we only talk about the “filtering” inference, which try to estimate the state at $\text{tim}e_{t}$, given all observation sequences at $\text{tim}e_{1:t}$. I.e., finding $P(X_{t} e_{1:t})$, where $X_{t}$ is the state at $\text{tim}e_{t}$(which box), $e$ is the observed evidence sequence for $\text{tim}e_{1:t}$ (which color). We use recurrent algorithm to calculate $P(X_{t} e_{1:t})$, let move one timestep ahead: $t = t + 1$. According to the Markov assumption and Bayesian rules, we can conclude: \[P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle| e_{1:t + 1} \right) = \alpha \cdot O_{t + 1} \cdot P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle| e_{1:t} \right)\]Here, $P\left( e_{t + 1} X_{t + 1} \right)$ we can get it from observation matrix B, it’s just the probability of observing evidence $e_{t + 1}$ given different state $X_{t + 1}$, we use $O_{t + 1}$ to replace it. \[P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle| e_{1:t + 1} \right) = \alpha \cdot O_{t + 1} \cdot \sum_{x_{t}}^{}{P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle| {x_{t},e}_{1:t} \right) \cdot P(x_{t}|e_{1:t})}\] \[= \alpha \cdot O_{t + 1} \cdot \sum_{x_{t}}^{}{P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle| x_{t} \right) \cdot P(x_{t}|e_{1:t})}\]But how to involve recurrent algorithm in above formula and make it as $P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle e_{1:t + 1} \right) = f\left( e_{t + 1},P\left( X_{t},e_{1:t} \right) \right)$. Let’s involve $x_{t}$ as condition then apply variable elimination algorithm to eliminate it. Note that according first-order Markov assumption, $X_{t + 1}$ only depends on $X_{t}$ and we have: \[P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle| e_{1:t + 1} \right) = \alpha \cdot O_{t + 1} \cdot T \cdot P(X_{t}|e_{t})\]Here, $P\left( X_{t + 1} \middle x_{t} \right)$ can be get from matrix $A$, which is the probability of next state $X_{t + 1}$ given current state $x_{t}$, we use T to replace it. Finally, we have the HMM filtering forward formula in a recurrent format. 15.3.2 hidden Markov model example: Localization

15.4 Kalman Filters

- 15.4.1 Updating Gaussian distributions

- 15.4.2 A simple one-dimensional example

- 15.4.3 The general case

- 15.4.4 Applicability of Kalman filtering

15.5 Dynamic Bayesian Networks

16 Making Simple Decisions

- 16.1 Combining Beliefs and Desires under uncertainty

- 16.2 The Basis of Utility Theory

16.2.1 Constraints on rational preference

In general, each outcome Si of a lottery can be either an atomic state or another lottery. The primary issue for utility theory is to understand how preferences between complex lotteries are related to preferences between the underlying states in those lotteries. To address this issue we list six constraints that we require any reasonable preference relation to obey:

- Orderability

- Transitivity

- Continuity

- Substitutability

- Monotonicity

- Decomposability

16.2.2 Preference lead to utility

Notice that the axioms of utility theory are really axioms about preferences—they say nothing about a utility function.

- Existence of Utility Function: If an agent’s preferences obey the axioms of utility, then there exists a function $U$ such that $U(A)>U(B)$ if and only if $A$ is preferred to $B$ and $U(A)=U(B)$ if and only if the agent is indifferent between $A$ and $B$

- Expected Utility of a Lottery: The utility of a lottery is the sum of the probability of each outcome times the utility of that outcome.

16.3 Utility Functions

- 16.3.1 Utility assessment and utility scales

16.3.2 The utility of money

Utility theory has its roots in economics, and economics provides one obvious candidate for a utility measure: money.

The value an agent will accept in lieu of a lottery is called the certainty equivalent of the lottery. Studies have shown that most people will accept about $400 in lieu of a gamble that gives $1000 half the time and $0 the other half—that is, the certainty equivalent of the lottery is $400, while the EMV is $500. The difference between the EMV of a lottery and its certainty equivalent is called the insurance premium.

16.3.3 Expected utility and post-decision disappointment

The rational way to choose the best action, $a^{*},$ is to maximize expected utility:

\[a^{*}=\underset{a}{\operatorname{argmax}} E U(a | \mathbf{e})\]This tendency for the estimated expected utility of the best choice to be too high is called the optimizer’s curse.

16.3.4 Human judgement and irrationality

Decision theory is a normative theory: it describes how a rational agent should act.

A descriptive theory, on the other hand, describes how actual agents really do act.

The best-known problem is the Allais paradox. People are given a choice between lotteries:

$A: 80 \%$ chance of $$ 4000$

$C: 20 \%$ chance of $$ 4000$

$B: 100 \%$ chance of $$ 3000$

$D: 25 \%$ chance of $$ 3000$

Most people consistently prefer $B$ over $A$ (taking the sure thing), and $C$ over $D$ (taking the higher EMV).In other words, there is no utility function that is consistent with these choices. One explanation for the apparently irrational preferences is the certainty effect: people are strongly attracted to gains that are certain.

Ⅴ Learning

18 Learning From Examples

18.1 Forms of Learning

Any component of an agent can be improved by learning from data. The improvements, and the techniques used to make them, depend on four major factors:

- which component is to be improved

- what prior knowledge the agent already has

- what representation is sued for the data and the component

- what feedback is available to learn from

Components to be learned

Some introduced agents include:

- A direct mapping from conditions on the current state to actions.

- A means to infer relevant properties of the world from the percept sequence.

- Information about the way the world evolves and about the results of possible actions the agent can take.

- Utility information indicating the desirability of world states.

- Action-value information indicating the desirability of actions.

- Goals that describe classes of states whose achievement maximizes the agent’s utility.

For instance, a taxi driver agent can learn when to brake, from every time the instructor shouts “Brake”.

Representation and prior knowledge

Representations for the components in a logical agent: propositional and first-order logical sentences.

Representations for the inferential components in a decision-theoretic agentBayesian networks: Bayesian networks.Feedback to learn from

There are three types of feedback that determine the three main types of learning:

- unsupervised learning: agent learns patterns in the input even though no explicit feedback is supplied

- reinforcement learning: agent learns from a series of reinforcements—rewards or punishments

- supervised learning: agent observes some example input–output pairs and learns a function that maps from input to output

18.2 Supervised Learning

The task of supervised learning is this: Given a training set of $N$ example input-output pairs \(\left(x_{1}, y_{1}\right),\left(x_{2}, y_{2}\right), \ldots\left(x_{N}, y_{N}\right)\) where each $y_{j}$ was generated by an unknown function $y=f(x)$ discover a function $h$ that approximates the true function $f$

The examples are points in the $(x, y)$ plane, where $y=f(x) .$ We don’t know what $f$ is, but we will approximate it with a function $h$ selected from a hypothesis space, $\mathcal{H},$. This illustrates a fundamental problem in inductive learning: how do we choose from among multiple consistent hypotheses? One answer is to prefer the simplest hypothesis consistent with the data. This principle is called Ockham’s razor.

In some cases, an analyst looking at a problem is willing to make more fine-grained distinctions about the hypothesis space, to say-even before seeing any data-not just that a hypothesis is possible or impossible, but rather how probable it is. Supervised learning can be done by choosing the hypothesis $h^{*}$ that is most probable given the data:

\(h^{*}=\underset{h \in \mathcal{H}}{\operatorname{argmax}} P(h | d a t a)\) By Bayes’ rule this is equivalent to \(h^{*}=\underset{h \in \mathcal{H}}{\operatorname{argmax}} P(d a t a | h) P(h)\)

There is a tradeoff between the expressiveness of a hypothesis space and the complexity of finding a good hypothesis within that space.

18.3 Learning Decision Trees

18.3.1 The decision tree representation

A decision tree represents a function that takes as input a vector of attribute values and returns a “decision”—a single output value.

- 18.3.2 Expressiveness of decision trees

18.3.3 Inducing decision trees from examples

18.3.4 Choosing attribute tests

We will use the notion of information gain, which is defined in terms of entropy, the fundamental quantity in information theory (Shannon and Weaver, 1949).

\[\text { Entropy: } \quad H(V)=\sum_{k} P\left(v_{k}\right) \log _{2} \frac{1}{P\left(v_{k}\right)}=-\sum_{k} P\left(v_{k}\right) \log _{2} P\left(v_{k}\right)\]We can check that the entropy of a fair coin flip is indeed 1 bit: \(H(\text {Fair})=-\left(0.5 \log _{2} 0.5+0.5 \log _{2} 0.5\right)=1\) If the coin is loaded to give $99 \%$ heads, we get \(H(\text {Loaded})=-\left(0.99 \log _{2} 0.99+0.01 \log _{2} 0.01\right) \approx 0.08 \text { bits. }\) It will help to define $B(q)$ as the entropy of a Boolean random variable that is true with probability $q:$ \(B(q)=-\left(q \log _{2} q+(1-q) \log _{2}(1-q)\right)\)

An attribute $A$ with $d$ distinct values divides the training set $E$ into subsets $E_{1}, \ldots, E_{d}$ Each subset $E_{k}$ has $p_{k}$ positive examples and $n_{k}$ negative examples, so if we go along that branch, we will need an additional $B\left(p_{k} /\left(p_{k}+n_{k}\right)\right)$ bits of information to answer the question. A randomly chosen example from the training set has the $k$ th value for the attribute with probability $\left(p_{k}+n_{k}\right) /(p+n),$ so the expected entropy remaining after testing attribute $A$ is

\(\text {Remainder }(A)=\sum_{k=1}^{d} \frac{p_{k}+n_{k}}{p+n} B\left(\frac{p_{k}}{p_{k}+n_{k}}\right)\) The information gain from the attribute test on $A$ is the expected reduction in entropy: \(\operatorname{Gain}(A)=B\left(\frac{p}{p+n}\right)-\text {Remainder}(A)\)

18.3.5 Generalization and overfitting

For decision trees, a technique called decision tree pruning combats overfitting. Pruning works by eliminating nodes that are not clearly relevant. We start with a full tree, as generated by DECISION-TREE-LEARNING.

How to choose a proper information gain threshold in order to split on a particular attribute? We can answer this question by using a statistical significance test. Such a test begins by assuming that there is no underlying pattern (the so-called null hypothesis).

We can measure the deviation by comparing the actual numbers of positive and negative examples in each subset - $p_k$ and $n_k$, with the expected numbers - $\hat{p}_k$ and $\hat{n}_k$, assuming true irrelevance:

\[\hat{p}_{k}=p \times \frac{p_{k}+n_{k}}{p+n} \quad \hat{n}_{k}=n \times \frac{p_{k}+n_{k}}{p+n}\]A convenient measure of the total deviation is given by:

\[\Delta=\sum_{k=1}^{d} \frac{\left(p_{k}-\hat{p}_{k}\right)^{2}}{\hat{p}_{k}}+\frac{\left(n_{k}-\hat{n}_{k}\right)^{2}}{\hat{n}_{k}}\]Under the null hypothesis, the value of $\Delta$ is distributed according to the $\chi^{2}$ (chi-squared) distribution with $v-1$ degrees of freedom. We can use a $\chi^{2}$ table or a standard statistical library routine to see if a particular $\Delta$ value confirms or rejects the null hypothesis. Which is known as $\chi^{2}$ pruning.

One final warning: You might think that χ2 pruning and information gain look similar, so why not combine them using an approach called early stopping—have the decision tree algorithm stop generating nodes when there is no good attribute to split on, rather than going to all the trouble of generating nodes and then pruning them away.

18.3.6 Broadening the applicability of decision trees

- Missing data

- Multivalued attributes

- Continues and integer-valued input attributes

- Continuous-valued output attributes

18.4 Evaluating and Choosing the Best Hypothesis

We make the stationarity assumption: that there is a probability distribution over examples that remains stationary over time. Each example data point (before we see it) is a random variable $E_{j}$ whose observed value $e_{j}=\left(x_{j}, y_{j}\right)$ is sampled from that distribution, and is independent of the previous examples:

\(\mathbf{P}\left(E_{j} | E_{j-1}, E_{j-2}, \ldots\right)=\mathbf{P}\left(E_{j}\right)\) and each example has an identical prior probability distribution: \(\mathbf{P}\left(E_{j}\right)=\mathbf{P}\left(E_{j-1}\right)=\mathbf{P}\left(E_{j-2}\right)=\cdots\)

Examples that satisfy these assumptions are called independent and identically distributed or i.i.d..

holdout cross-validation: randomly split the available data into a training set from which the learning algorithm produces h and a test set on which the accuracy of h is evaluated. This method, sometimes called holdout cross-validation.

k-fold cross-validation: We can squeeze more out of the data and still get an accurate estimate using a technique called k-fold cross-validation. The idea is that each example serves double duty—as training data and test data.

leave-one-ouut cross-validation(LOOCV): The extreme is k = n, also known as leave-one-out cross-validation or LOOCV.

peeking at the test data: Peeking can happen like this: A learning algorithm has various “knobs” that can be twiddled to tune its behavior—for example, various different criteria for choosing the next attribute in decision tree learning. The researcher generates hypotheses for various different settings of the knobs, measures their error rates on the test set, and reports the error rate of the best hypothesis.

- 18.4.1 Model selection: Complexity versus goodness of fit

18.4.2 From error rates to loss

Absolute value loss: $L_{1}(y, \hat{y})=|y-\hat{y}|$

Squared error loss: $\quad L_{2}(y, \hat{y})=(y-\hat{y})^{2}$

$0 / 1$ loss: $\quad L_{0 / 1}(y, \hat{y})=0$ if $y=\hat{y},$ else 1generalization loss:

\[\operatorname{Gen} \operatorname{Loss}_{L}(h)=\sum_{(x, y) \in \mathcal{E}} L(y, h(x)) P(x, y)\]and the best hypothesis, $h^{*},$ is the one with the minimum expected generalization loss:

\[h^{*}=\underset{h \in \mathcal{H}}{\operatorname{argmin}} \operatorname{Gen} \operatorname{Loss}_{L}(h)\]Because $P(x, y)$ is not known, the learning agent can only estimate generalization loss with empirical loss on a set of examples, $E:$

\[EmpLoss_{L, E}(h)=\frac{1}{N} \sum_{(x, y) \in E} L(y, h(x))\]The estimated best hypothesis $\hat{h}^{*}$ is then the one with minimum empirical loss:

\[\hat{h}^{*}=\underset{h \in \mathcal{H}}{\operatorname{argmin}} \operatorname{Emp} \operatorname{Loss}_{L, E}(h)\]18.4.3 Regularization

A alternative approach is to search for a hypothesis that directly minimizes the weighted sum of empirical loss and the complexity of the hypothesis, which we will call the total cost:

\[\begin{aligned} \operatorname{cost}(h) &=E m p \operatorname{Loss}(h)+\lambda \text { Complexity }(h) \\ \hat{h}^{*} &=\underset{h \in \mathcal{H}}{\operatorname{argmin}} \operatorname{Cost}(h) \end{aligned}\]

18.5 The Theory of Learning

Q1: how many examples are needed for learning?

Learning curves are useful, but they are specific to a particular learning algorithm on a particular problem. Are there some more general principles governing the number of examples needed in general? Questions like this are addressed by computational learning theory. The underlying principle is that any hypothesis that is seriously wrong will almost certainly be “found out” with high probability after a small number of examples, because it will make an incorrect prediction. Thus, any hypothesis that is consistent with a sufficiently large set of training examples is unlikely to be seriously wrong: that is, it must be probably approximately correct(PAC).

Any learning algorithm that returns hypotheses that are probably approximately correct is called a PAC learning algorithm.

Thus, if a learning algorithm returns a hypothesis that is consistent with this many examples, then with probability at least 1 − δ, it has error at most ε. In other words, it is probably approximately correct.

The number of required examples, as a function of ε and δ, is called the sample complexity of the hypothesis space.

18.6 Regression and Classification with Linear Models

18.6.1 Univariate linear regression

\[h_{\mathbf{w}}(x)=w_{1} x+w_{0}\] \[\operatorname{Loss}\left(h_{\mathbf{w}}\right)=\sum_{j=1}^{N} L_{2}\left(y_{j}, h_{\mathbf{w}}\left(x_{j}\right)\right)=\sum_{j=1}^{N}\left(y_{j}-h_{\mathbf{w}}\left(x_{j}\right)\right)^{2}=\sum_{j=1}^{N}\left(y_{j}-\left(w_{1} x_{j}+w_{0}\right)\right)^{2}\]We would like to find $\mathbf{w}^{*}=\operatorname{argmin}{\mathbf{w}} \operatorname{Loss}\left(h{\mathbf{w}}\right) .$ The sum $\sum_{j=1}^{N}\left(y_{j}-\left(w_{1} x_{j}+w_{0}\right)\right)^{2}$ is minimized when its partial derivatives with respect to $w_{0}$ and $w_{1}$ are zero:

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial w_{0}} \sum_{j=1}^{N}\left(y_{j}-\left(w_{1} x_{j}+w_{0}\right)\right)^{2}=0 \text { and } \frac{\partial}{\partial w_{1}} \sum_{j=1}^{N}\left(y_{j}-\left(w_{1} x_{j}+w_{0}\right)\right)^{2}=0\]These equations have a unique solution:

\[w_{1}=\frac{N\left(\sum x_{j} y_{j}\right)-\left(\sum x_{j}\right)\left(\sum y_{j}\right)}{N\left(\sum x_{j}^{2}\right)-\left(\sum x_{j}\right)^{2}} ; w_{0}=\left( \sum y_{j}-w_{1}( \sum x_{j}) \right) / N\]In this case, because we are trying to minimize the loss, we will use gradient descent:

$\mathbf{w} \leftarrow$ any point in the parameter space

loop until convergence do

for each $w_{i}$ in w do \(w_{i} \leftarrow w_{i}-\alpha \frac{\partial}{\partial w_{i}} \operatorname{Loss}(\mathbf{w})\)The parameter α, which we called the step size, is usually called the learning rate.

For univariate regression:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial}{\partial w_{i}} \operatorname{Loss}(\mathbf{w}) &=\frac{\partial}{\partial w_{i}}\left(y-h_{\mathbf{w}}(x)\right)^{2} \\ &=2\left(y-h_{\mathbf{w}}(x)\right) \times \frac{\partial}{\partial w_{i}}\left(y-h_{\mathbf{w}}(x)\right) \\ &=2\left(y-h_{\mathbf{w}}(x)\right) \times \frac{\partial}{\partial w_{i}}\left(y-\left(w_{1} x+w_{0}\right)\right) \end{aligned}\]applying this to both $w_0$ and $w_1$ we get:

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial w_{0}} \operatorname{Loss}(\mathbf{w})=-2\left(y-h_{\mathbf{w}}(x)\right) ; \quad \frac{\partial}{\partial w_{1}} \operatorname{Loss}(\mathbf{w})=-2\left(y-h_{\mathbf{w}}(x)\right) \times x\]batch gradient descent:

\[w_{0} \leftarrow w_{0}+\alpha \sum_{j}\left(y_{j}-h_{\mathbf{w}}\left(x_{j}\right)\right) ; \quad w_{1} \leftarrow w_{1}+\alpha \sum_{j}\left(y_{j}-h_{\mathbf{w}}\left(x_{j}\right)\right) \times x_{j}\]stochastic gradient descent: consider only a single training point at a time, taking a step after each one.

18.6.2 Multivariate linear regression

\[h_{s w}\left(\mathbf{x}_{j}\right)=\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}_{j}=\mathbf{w}^{\top} \mathbf{x}_{j}=\sum_i w_{i} x_{j, i}\] \[\mathbf{w}^{*}=\underset{\mathbf{w}}{\operatorname{argmin}} \sum_{j} L_{2}\left(y_{j}, \mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}_{j}\right)\] \[w_{i} \leftarrow w_{i}+\alpha \sum_{j} x_{j, i}\left(y_{j}-h_{\mathbf{w}}\left(\mathbf{x}_{j}\right)\right)\]It is also possible to solve analytically for the w that minimizes loss. Let $\mathbf{y}$ be the vector of outputs for the training examples, and $\mathbf{X}$ be the data matrix, i.e., the matrix of inputs with one $n$ -dimensional example per row. Then the solution

\[\mathbf{w}^{*}=\left(\mathbf{X}^{\top} \mathbf{X}\right)^{-1} \mathbf{X}^{\top} \mathbf{y}\]minimizes the squared error.

For linear functions the complexity can be specified as a function of the weights. We can consider a family of regularization functions:

\[\text { Complexity }\left(h_{\mathbf{w}}\right)=L_{q}(\mathbf{w})=\sum_i\left|w_{i}\right|^{q}\]18.6.3 Linear classifiers with a hard threshold

18.6.4 Linear classification with logistic regression

\[\text {Logistic}(z)=\frac{1}{1+e^{-z}}\] \[h_{\mathbf{w}}(\mathbf{x})=\text {Logistic}(\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})=\frac{1}{1+e^{-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}}}\] \[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial}{\partial w_{i}} \operatorname{Loss}(\mathbf{w}) &=\frac{\partial}{\partial w_{i}}\left(y-h_{\mathbf{w}}(\mathbf{x})\right)^{2} \\ &=2\left(y-h_{\mathbf{w}}(\mathbf{x})\right) \times \frac{\partial}{\partial w_{i}}\left(y-h_{\mathbf{w}}(\mathbf{x})\right) \\ &=-2\left(y-h_{\mathbf{w}}(\mathbf{x})\right) \times g^{\prime}(\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}) \times \frac{\partial}{\partial w_{i}} \mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x} \\ &=-2\left(y-h_{\mathbf{w}}(\mathbf{x})\right) \times g^{\prime}(\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}) \times x_{i} \end{aligned}\] \[g^{\prime}(\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})=g(\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})(1-g(\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}))=h_{\mathbf{w}}(\mathbf{x})\left(1-h_{\mathbf{w}}(\mathbf{x})\right)\] \[w_{i} \leftarrow w_{i}+\alpha\left(y-h_{\mathbf{w}}(\mathbf{x})\right) \times h_{\mathbf{w}}(\mathbf{x})\left(1-h_{\mathbf{w}}(\mathbf{x})\right) \times x_{i}\]However, in practice, we use LogLoss instead of MSELoss.

\[-(y \log (p)+(1-y) \log (1-p))\]

18.8 Nonparametric Models

That defines our hypothesis hw(x), and at that point we can throw away the training data, because they are all summarized by w. A learning model that summarizes data with a set of parameters of fixed size (independent of the number of training examples) is called a parametric model.